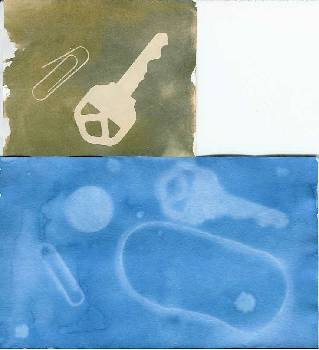

Originally posted by hodges

That was before I got my homemade ferric oxalate blueprint process working. If I had known I would get it to work I would not have necessarily

ordered anything else. The amounts needed are truly tiny. I used around 2.5 grams of ferrous sulfate, 2g total of oxalic acid, and 1g of potassium

ferricyanide. This makes two 10ml solutions which are mixed and right before application. |