Boffis

International Hazard

Posts: 1897

Registered: 1-5-2011

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

The purification of old p-Benzoquinone

Benzoquinone is not completely stable and slowly, over time, turns dark green and eventually black. The colour is probably due to quinhydrone, a 1:1

molecular complex between p-benzoquinone and hydroquinol but other substances such as a reddish brown uncrystallisable material are also present.

When p-benzoquinone has been freshly prepared it is usually an easy job to purify it by recrystallization from various solvent such as methanol (about

1.5ml per gram) or high boiling range petroleum ether (100-120°C; about 30-35ml per gram). In the case of the former solvent it is not good at

removing dark impurities, presumed to be mainly quinhydrone, and in the case of the latter it requires the use of large volumes of solvent which make

recrystallizing tedious if large quantities of benzoquinone are involved.

Some years ago I acquired a large jar of p-benzoquinone supplied by Aldrich, it had originally contained 1kg but now appears to contain about

600-700g. The vintage of the material is not known but the provider did say that it was old and had turn black. Attempts to recrystallize it proved to

be both messy and tedious or failed to give a pure yellow product.

Recently I required some pure benzoquinone for some Diels Alder type reaction and was once again moved to purify some of this material. Looking at the

various published methods 1) 2) I decided to try steam distillation first, this worked well, gave an excellent product but it took a week

to dry adequately to be usable in my reaction. In Woodward’s paper 2) they used a Soxhlet extractor with octane as the extractant but

when I tried this I had no octane so I tried it with n-heptane with a Bp. range of about 95-100°C. I found the boiling point of heptane was too high

and after a while the benzoquinone began to distil with the solvent and deposit in the condenser; the Bp. of n-octane is about 115°C so this problem

is likely to be worse. I then ran a series of experiments with lower boiling fractions of petroleum ether, first 40-60°C boiling range and then

60-80°C boiling range ether. The 40-60°C boiling petroleum ether worked well but was slow with one extraction taking 5-6 hours but the 60-80°C

boiling range petroleum ether proved to be ideal giving reasonably rapid extraction, high recovery and a product that dries quickly.

Steam Distillation

The equipment used for this process comprised a 1L round-bottom flask in a heating mantle as a steam generator. This was connected to the distillation

flask which consisted of a two-neck round bottom 500ml flask via a steam injector tube in one neck. The other neck had a simple still-head connected

to a short, 25cm air-condenser. A receiving horn adapter on the condenser led into a beaker of ice and water standing in an ice bath. If a water

flushed condenser is used the benzoquinone tends to choke the lower part of it. The air condenser was cooled with a wet cloth that was periodically

moistened with water. The distillation flask also stood in a heating mantle to augment the heat input and reduce the amount of injected water required

but this is probably not necessary.

Left: Steam distillation set up. Middle: Distilled benzoquinone slurry. Right: Benzoquinone filtered product

The steam generator was charged with 600ml of water while 150ml of warm water and about 30g of the crude black benzoquinone were placed in the

distillation flask. Steam was passed into the distillation flask until no further benzoquinone appeared to be passing over, about 2 hours. The

receiving beaker was arranged so that the receiver just dipped into the water. The beaker contained about 100ml of chilled water and ice cubes and

further ice cubes were added to the bath as distillation continued. It was necessary to change the receiving beaker periodically as the volume of melt

water and distillate tended to fill them. Only about 250-300ml of water were used in the distillation.

Once distillation was complete the steam was turned off and the combined distillates chilled in the fridge to about 4°C. The bright lemon yellow

crystalline solid was filtered off, sucked as dry as possible and finally dried in a desiccator over calcium chloride for a week. In a typical run

30.35g of crude benzoquinone gave 15.63g of pure benzoquinone, a recovery of about 51%. Recoveries ranged from 47 to 52%. The residue in the flask was

a very dark brown viscous gooey tar that was hell to remove. The best materials were strong caustic soda solution or copious >8% bleach for 24

hours. The clean-up is probably the major drawback of this procedure though a further disadvantage is the slow drying of the benzoquinone because of

its volatility at even slightly elevated temperatures. The benzoquinone must be dried at as low temperature as possible.

Soxhlet Extraction

A typical extraction using petroleum ether, boiling range 60-80°C, was as follows:

A standard Soxhlet extractor comprising a 500ml boil flask (note 1), an extractor unit taking 20x80mm paper thimbles and Liebig condenser was set up

in a heating mantle. The flask was charged with 300ml of petroleum ether and 21.44g of crude benzoquinone were placed in the thimble. A small wad of

cotton wool was placed on top of the charge to prevent splash-out of the benzoquinone by the drops of solvent from the condenser. The flask was

brought gently to the boil and the boiling rate then adjusted to give a steady and fairly rapid stream of drops of solvent from the condenser. The

extraction was run for about 2.5 to 3 hours then allowed to cool to about 25°C before being dismantled. The contents of the flask were poured into a

tall-form beaker and some of the supernatant liquor used to rinse the flask a couple of times. The solution was allowed to cool to about 10° C but

not more (note 3) and filtered through a Hirsch funnel and sucked dry. The filtrate was returned to the flask and the extraction continued for a

further hour until the leachate was almost colourless, this helps ensure that no benzoquinone crystals are left in the syphon on cooling. The final

leachate was cool a little, poured into the same beaker as before and chilled to 3-4°C. The crystals being recovered by filtration as before.

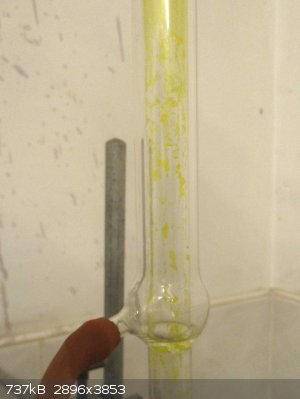

Left: Soxhlet extraction set up. Right: Benzoquinone depositing in the condenser when n-heptane as used as the solvent.

The first crop of crystals was 19.36g and this represent a recovery of about 90%, a recovery of 85-87% was more typical (note 4), and the product was

a beautiful golden yellow needles. The second crop was 1.57g but was contaminated with some dark crystals. This material was added back to the next

batch.

Golden yellow prismatic benzoquinone crystallizing in the boiling flask

The thimbles may be washed almost clean with methanol and reused a second time and sometime even a third time. Eventually black blisters appear in the

cellulose and the thimbles begin to loose there integrity. If the methanol washings are distilled and the final deep red residue allowed to partly

evaporate in the cold a small additional crop of impure benzoquinone can be recovered but it is barely worth it.

Discussion

Steam distillation is fairly quick and with my equipment I can handle larger quantities. Although roughly 30g were used in the experiment described

above at least 60g can be accommodated though the yield was slightly less. The main issue with steam distillation is that the highly volatile

benzoquinone takes a long time to dry over calcium chloride and may still contain a little water. There is also an issue with benzoquinone vapour

escaping from the receiving adapter when the beaker is changes or if the condenser gets too hot, the procedure requires constant attention.

Furthermore the recovery is typically about 50% and the flask residue contains much gooey tar.

Steam distilled benzoquinone (left) and pet. ether (Bp 60-80) soxhlet extracted product (right)

Soxhlet extraction of the crude benzoquinone gives a much higher recovery of material that is easily dried, with 40-60° boiling range petroleum ether

constant weight is achieved in 20 minutes and with 60-80 boiling range ether in a little over an hour. Once the equipment is running at steady state

it can be left for up to 2 hours with minimal attention. Recovery is typically 85-90% with the first crop of crystals but by recycling the small

second crop into the next batch this can be raised to 90-95%. The disadvantages are that with the equipment I have the maximum charge per extraction

is only 20-22g and the quality of the product is slightly lower in terms of dark material being present. One big advantage though, is that the

equipment is easily cleaned. The equipment is simply allowed to dry to remove the petroleum and then rinsed in dilute sodium bisulphite solution! No

horrible gooey tar from hell. About 80% of the petroleum ether can be recovered by swirling periodically with a small amount of 1M sodium bisulphite

solution and standing for about 12 hours, separating the ether, dry with calcium chloride or magnesium sulphate and distil, Note 5.

Conclusion

For experiments that are to be conducted in an aqueous environment such as the preparation 2,3-dicyanobenzoquinone, hydroquinone sulphonic acid,

haloquinols and the corresponding quinones steam distillation has the advantages of simplicity of equipment and procedure. Where the benzoquinone is

to be used in anhydrous or non-aqueous environments such as the Diels Alder reaction in benzene the solvent extraction method is probably preferable

if the equipment is available. Solvent extraction gives a significantly better recovery; 85% or more as against about 50% by steam distillation.

Note 1, to start with a 1000ml flask was used with only 200ml of solvent but this was found to result in a rim of product building up

below the level of the top of the heating mantle causing scorching of the benzoquinone. More solvent and a smaller 500ml flask greatly reduced this

problem. No bumping was encountered in spite of the fact that no stirrer was used.

Note 2, the ground glass neck of the boiling flask was rinsed with fresh warm petroleum ether to ensure it didn’t seize later.

Note 3, if the first extract is cooled below about 10-12° that last formed crystals have dark edges or inclusions. It is better to

let these impurities be caught in the last crop and they can then be advantageously recycled into a later batch.

Note 4, looking at all of the batches with this boiling range (60-80°) petroleum ether the optimum extraction time for the first

crop is 2½ hours plus a further 1¼ hours for the second extraction. This gives about 85% recovery in the first crop but the quality is better. The

second crop of about 8-10% is always discoloured particularly if the extract is chilled to 4°C or so.

Note 5, it is important that when multiple extractions are run back to back that fresh solvent is used each time as some dark

impurities accumulate in petroleum ether.

1) Armarengo & Chai; Purification of Laboratory Chemicals, 6th Ed; 2009.

2) Woodward et al.; The total synthesis of reserpine; Tetrahedron; v2; p1-57 [1958].

|

|

|

kmno4

International Hazard

Posts: 1517

Registered: 1-6-2005

Location: Silly, stupid country

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

I have performed similar experimets recently, because long time ago I used up all my BQ ( BTW, it was by mistake, hah) and now I need it again.

I have very old hydroquinone (photo grade) and I made oxidation in two independent ways: chromate in sulfuric acid sol. and KClO3+NH4VO3(cat) in

sulfuric acid sol. Both methods gave not looking good BQ - yellow-green-dark grey crystalline dust after drying.

The sublimation setup was very simple: large glass jar (~ 3 dm3) placed on hot plate. The outlet of the jar was "plugged" with RBF filled with water.

Prepared raw BQ was placed inside the jar of course and heating started. Sublimation was rather slow below ~60-70 C (bottom of the jar) and the

temperature was increased to about ~90-100 C. Yellow, crystalline BQ covered inside walls of the jar and bottom of RBF. From time to time, the jar was

set aside, colled a little and most of collected BQ was removed by long metal spoon as final product. This procedure was repeated several times

(depends on input amount of raw BQ). No foto is taken, the sublimate looks exactly as showed by Boffis: yellow or orange-yellow (in lager crystals)

powder.

At the end of sublimation, the sublimate was not so pure, the yellow layer attained darker shade with almost black points.

What warried me: amount of almost black residue inside the jar corresponds to not less than ~15 % of input raw material. It is rather large amount of

by product, caused possibly by impurity of starting hydroquinone. This residue, reduced by Na2S2O4 in water gives brown, not transparent "solution" of

who-knows-what.

That is all wanted to report, no m.p. was measured

Слава Україні !

Героям слава !

|

|

|

Fery

International Hazard

Posts: 1052

Registered: 27-8-2019

Location: Czechoslovakia

Member Is Offline

|

|

here they also used sublimation:

https://youtu.be/IRxijp-jh_o?t=210

I've bought these coldfinger condensers 2 years ago here:

https://sklep-chemland.pl/en/szklo-laboratoryjne/chlodnice/c...

all short are sold (200, 300, 400, 500 mm), only unpractical too long 600 mm available currently

|

|

|

|