Metallus

Hazard to Others

Posts: 116

Registered: 16-5-2013

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Help identifying these metal ions

Hello,

recently I stumbled upon a test for metal ions that puzzled me. The starting compound is the residue of coal waste, treated with KOH, which looks like

a mix of iron oxides (pale green/brown), but it reacts in odd ways, which suggests there might be other things in there.

When dissolved in water, it has a pH > 13 due to a large excess of potassium hydroxide in the solution

• A first, concentrated batch was dissolved in water and was dark emerald green, but after a day at room temperature, it turned yellow and there was

no precipitate formation.

• After a couple of days, a second less concentrated batch was dissolved in water, but this time it was a paler green and not fully clear.

Acidifying with HCl led to violent foaming (likely due to the decomposition of carbonates) and turned the solution from pale green to bright yellow.

• Adding H2O2 to this solution led to the formation of a deep blue solution, which rapidly became colorless (within 2s).

The suspect metal ions are Fe and Cr mainly, but some things don't sound right:

1) In the starting green solution (pH >13), if it was Fe(II), it would make sense that it undergoes oxidation with air overtime and turns into

Fe(III), but shouldn't the high pH make Fe(III) precipitate?

2) Dissolving a new batch yielded a paler green solution. If it was Fe(II), it could be that the 2nd batch underwent some oxidation on its own

overtime; acidifying this solution with HCl instantly turned it into a bright yellow which could be due to the oxidation of Fe(II) to Fe(III).

3) Adding H2O2 turned the solution from yellow to a deep blue, before becoming completely colorless. The acid solution of Cr(VI) is known to

temporarily make a deep blue complex with H2O2, that rapidly decomposes back to green Cr(III), but this one becomes completely colorless. Also, if it

was Cr (VI), where would that come from? What can oxidise Cr III to VI in such conditions?

Do you have any idea what it might be and why it behaves like this?

|

|

|

j_sum1

Administrator

Posts: 6338

Registered: 4-10-2014

Location: At home

Member Is Offline

Mood: Most of the ducks are in a row

|

|

Looks like Cr plus something oxidising in the mix.

|

|

|

Admagistr

Hazard to Others

Posts: 376

Registered: 4-11-2021

Location: Central Europe

Member Is Offline

Mood: The dreaming alchemist

|

|

I also immediately thought of chromium, but why is the solution colourless afterwards?! So Cr3+ doesn't behave like that... Is any chromium compound

colourless, I highly doubt it!

[Edited on 2-5-2023 by Admagistr]

|

|

|

clearly_not_atara

International Hazard

Posts: 2801

Registered: 3-11-2013

Member Is Offline

Mood: Big

|

|

Mo (V) is blue, and Mo (VI) can be colorless.

|

|

|

j_sum1

Administrator

Posts: 6338

Registered: 4-10-2014

Location: At home

Member Is Offline

Mood: Most of the ducks are in a row

|

|

I thought of that. But the blue is a bit different. And that does not explain the green, which is quite an intense forest green.

|

|

|

DraconicAcid

International Hazard

Posts: 4363

Registered: 1-2-2013

Location: The tiniest college campus ever....

Member Is Offline

Mood: Semi-victorious.

|

|

Dilute chromium(III) is pretty close to colourless, especially compared to the intensity of the peroxide complex.

Please remember: "Filtrate" is not a verb.

Write up your lab reports the way your instructor wants them, not the way your ex-instructor wants them.

|

|

|

kmno4

International Hazard

Posts: 1504

Registered: 1-6-2005

Location: Silly, stupid country

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

It looks like Cr, of course, but with some admixture.

This admixture(s) may catalyze air oxidation of Cr(III) to Cr(VI) - for example Mn does this trick.

About colourless solution - it reminds me Ni(II) and Co(II) mixture.

At some ratio Ni/Co, the solution is purely colourless. It may be similar case.

Слава Україні !

Героям слава !

|

|

|

j_sum1

Administrator

Posts: 6338

Registered: 4-10-2014

Location: At home

Member Is Offline

Mood: Most of the ducks are in a row

|

|

This is not my experience. I have often been surprised by the intensity of Cr(iii) solutions.

|

|

|

Metallus

Hazard to Others

Posts: 116

Registered: 16-5-2013

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Thanks for your replies

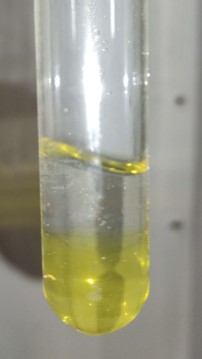

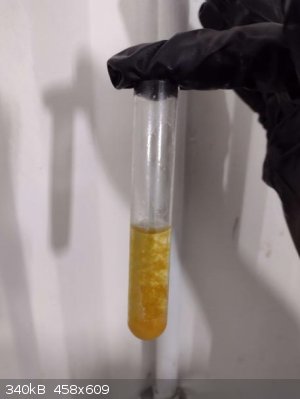

Another update on this test. One of the batch of the pale green solution was left overnight and the following day it was bright yellow. To this, H2O2

was added while the solution was still basic, but nothing happened. But after the addition of some acid, part of the solution became blue/purple and

then turned colorless, but the most interesting thing is... it separated!

As you can see from the pictures, the colorless liquid is floating on top of the yellow one (which is still basic). Adding extra acid, makes the

remaining yellow react and go to blue and colorless and mix with the rest.

What could this immiscible colorless liquid be? So far we hypothesized it was a reaction of Cr VI making the blue peroxocomplex and then going to Cr

III, but then the solution should be green, but instead it's colorless and not miscible with water. Any idea?

One additional detail, the basic yellow solution reacts with organic matter like cellulose from wood and turns orange with some brown precipitate, but

this could be gunk from the wood bits.

|

|

|

woelen

Super Administrator

Posts: 8034

Registered: 20-8-2005

Location: Netherlands

Member Is Offline

Mood: interested

|

|

The floating on top is most likely due to difference in density. If you have miscible liquids, but one of them is denser than the other, then they

remain separated for quite a while, but slowly they will diffuse into each other.

I think that there is chromium in the mix, but that is not the complete story. The blue color with H2O2 at low pH and the fading of that color is

quite specific for hexavalent chromium. Even very dilute hexavalent chromium can be detected this way. Iron could also be present. If you have

potassium ferrocyanide (yellow prussiate of potash, K4Fe(CN)6), then you could try adding some of that. With trivalent iron it gives an intense blue

color or low to medium pH, which persists. At high pH, the blue color disappears and the liquid turns pale yellow/brown and a little opalescent.

|

|

|

Metallus

Hazard to Others

Posts: 116

Registered: 16-5-2013

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Update

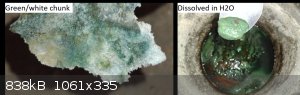

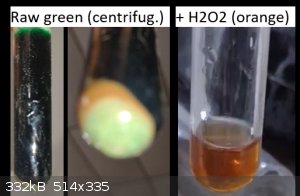

A dried green/white chunk of the raw material was dissolved in water, yielding a rusty precipitate, a dark green solution and some whitish suspension

(this solid contains KOH and its pH is >13). This was centrifuged, forming 2 precipitates (a whitish and orange one) and leaving a very intense

dark green solution. The dark green solution was isolated.

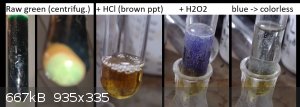

1) to 1 ml of this dark green solution, HCl was added, turning the solution yellow and producing a brown precipitate (acid pH). To the resulting

solution, H2O2 was added, initially turning the solution blue (for 1s) and then pale green/colorless (a separation of the two liquids was observed, as

shown in the previous post).

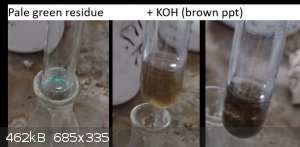

On the pale green/colorless solution, KOH was added again to bring the pH back to 13, turning the solution fully colorless and producing a dark brown

precipitate.

2) to 1 ml of the starting dark green solution, H2O2 was added, turning the solution dark orange.

Hypothesis:

1) The starting solution has an intense dark green color, and the only thing I know that is so intensely colored is Cr III, likely in the form of

Cr(OH)63- due to the very basic pH.

- Acidifying this solution turns it yellow, with a brown precipitate. The yellow could be attributed to the formation of CrO42-,

but which species could be oxidising Cr III to VI, while leaving behind a brown precipitate?

- My hypothesis is that there is some MnO4- or MnO42- in there (the latter being green too!), and that

acidifying the solution leads to the oxidation of Cr III to Cr VI, and the reduction of Mn VI/V to Mn IV, which precipitates as MnO2 (brown

precipitate).

- Then, following the addition of H2O2 in acid environment, the CrO42- (and MnO2) are reduced to Cr3+ and

Mn2+, which leave a pale green/colorless solution.

- Upon addition of KOH, a dark brown solid precipitates. Now, I'm not sure why this is happening. Could it be that the excess H2O2, coupled with the

basic pH, is oxidising Mn2+ to MnO2? Usually H2O2 is a strong oxidiser in basic pH (or more precisely, these metal oxides are less

oxidising in basic environments), so that would explain the brown precipitate.

2) Upon addition of H2O2 to the raw, basic, dark green solution, the solution turns dark orange. If the H2O2 was oxidising Cr III to Cr VI, this

should be bright yellow instead of dark orange (which is typical of acid Cr VI solutions), and if there was Mn in there, not much should happen. The

only metal that turns orange in basic H2O2 solutions that I know of, is lead IV/II oxide (Pb3O4).

Do you have any observations or thoughts about what else could be in there?

|

|

|

j_sum1

Administrator

Posts: 6338

Registered: 4-10-2014

Location: At home

Member Is Offline

Mood: Most of the ducks are in a row

|

|

Ti forms an amber complex with peroxide.

I think your detective work is good here. But it seems there is quite a mixture in there.

|

|

|

Metallus

Hazard to Others

Posts: 116

Registered: 16-5-2013

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Some more weird things

The starting green, basic solution, becomes yellow overtime on its own. Adding HCl to this solution leads to the formation of a brown precipitate AND

negative pressure. It's like it's consuming something from the atmosphere. As you can see in the pictures below, the glove is being sucked in. What

could be causing that? I thought oxygen consumption from the air might be the reason, but shouldn't oxygen diffusion be a slow process anyways for

this to be noticeable?

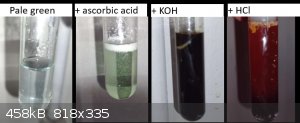

Some other tests on the pale green solution, obtained after HCl + H2O2 treatment, which in theory should have left a Cr3+ solution behind

(the excess H2O2 was previously decomposed by heating):

- in one test tube of the pale green solution, adding ammonia till basic pH leads to the formation of a light blue/azure precipitate. After

centrifugation, it still doesn't fully settle and remains suspended as a light blue gel. Upon addition of KOH, a dense gas is released (probably

ammonia) and a brown precipitate forms. After centrifugation, this settles as a brown solid, leaving a pale brown solution.

- in another test tube of the pale green solution, adding ascorbic acid turns the solution light green, and adding KOH afterwards turns it very

dark/black with an olive/red weird tint. Adding HCl, makes the solution lighter colored, revealing a dark red hue.

1) If the HCl + H2O2 left a Cr3+ solution, adding a weak base should make green Cr(OH)3 precipitate, but instead an azure

precipitate is obtained. Could this be an amino-compound with Cr? I remember seeing something similar in Woelen's wegpage about Cr III. Adding KOH

should in theory reverse the entire reaction and take us back to the starting dark green solution, hypothesized to be Cr(OH)63-,

instead a dark brown precipitate forms.

2) Due to the acid pH, ascorbic acid should be in its protonated form and shouldn't be acting as a chelating agent, but could still be acting as a

reductant. Are you aware of a reaction that turns pale green to light green? Adding KOH makes a very dark solution, that lightens up only upon

addition of HCl.

I still think there's some Cr in there (because of the temporary blue complex) but what else could be giving these reactions? And why are we unable to

revert back to the dark green solution?

Is anyone familiar with ascorbic acid and what metal complexes it might make? Or perhaps if in these conditions it is acting as a reductant. Are any

of these colors familiar?

[Edited on 5-5-2023 by Metallus]

|

|

|

Boffis

International Hazard

Posts: 1886

Registered: 1-5-2011

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

First of all what do you mean by "coal waste"? Some younger low rank coals have accumulated much vanadium and uranium. I worked on such deposits in

Central Asia, some of them were mined in soviet times for uranium. The coal was burnt in a power plant then the ash processed to recovery the uranium

and vanadium.

Deposits of this type exist in the USA too and probably else where. The grade is usually too low to be mined for the metals alone but they are greatly

enriched in the ash.

So, as you can see there is a lot of scope, Zn, Se, Ge and various other base metals are not uncommon in some coals. If the coal "waste" hasn't been

burnt but weathered at the surface organic phases are possible too. I worked on a project once where cores from the weathered zone of oil shale near

Edinburgh in Scotland would "bleed" a beautiful purple colour is treated with alkali. The fresh shale didn't seem to do this.

So what exactly is your coal waste?

[Edited on 5-5-2023 by Boffis]

|

|

|

kmno4

International Hazard

Posts: 1504

Registered: 1-6-2005

Location: Silly, stupid country

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

..... that is why I would use XRF spectrometer to analyse the raw material. Playing with probes gives more questions than answers.

At best, one or two main metals can be identified in this way.

One should use more specific tests, in better controlled conditions.

The colour of sediment on the first picture strongly reminds me sediments obtained during my experiments with Cr(III) performed long time ago, but it

is only my personal impression.

Слава Україні !

Героям слава !

|

|

|

j_sum1

Administrator

Posts: 6338

Registered: 4-10-2014

Location: At home

Member Is Offline

Mood: Most of the ducks are in a row

|

|

This recently-posted yt clip seems relevant. It looks like a lot of what you have observed is happening here.

https://youtu.be/UeypljpiB-U

One of the things that confused me is the colourless solution containing Cr(iii). My experience of Cr3+ is that the colour is quite intense and I am

never expecting colourless. Perhaps the presence of sulfate makes a difference: Cr2(SO4)3 has a very rich colour.

|

|

|