| Pages:

1

2

3 |

MrHomeScientist

International Hazard

Posts: 1806

Registered: 24-10-2010

Location: Flerovium

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

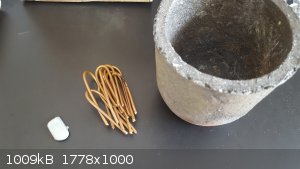

Making Pinchbeck Brass

Not so much chemistry as metallurgy, but I thought people might be interested anyway. I tried making some brass this afternoon by alloying copper and

zinc in my furnace. My goal is to make a brass that looks very similar to gold, for use in another project. Obviously I could just go buy some brass

fittings, but I thought it would be fun and educational to try making it instead.

Researching brass alloy colors led me to Pinchbeck, an alloy designed to resemble gold (some neat history on it in that link). It has a copper:zinc ratio of either 89:11 or 93:7.

One of the difficulties in making brass is that zinc's boiling point (907 C) is actually lower than copper's melting point (1084 C). So the

way to make this alloy (and many others, from what I've read) is to melt the highest-melting component first, then add in the other components in

descending order of melting point. With zinc you get a "flare-up" and a lot of it boils off, so you hope that most of it dissolves in the melt first.

This article at Scientific American has some good info too.

I started with 113.43g Cu and 14.0g Zn to go for the 89% copper ratio, assuming that some zinc would boil off and drive it closer to the 93% ratio.

I also read a bit about brass fluxing; there's a nice chapter on it here. I tried sprinkling some crushed charcoal over the copper prior to melting. I'm not sure if it did anything though; I'm thinking I probably

should have done that after it was melted.

Side note about safety: vaporized zinc is not great to breathe. NIOSH recommends an N95 particulate filter for zinc oxide fumes. I wore one of those in addition to all my heat safety gear.

Anyways, I heated the copper until molten and then dropped the piece of zinc on to the melt. Being less dense, it floated on top and less than a

second later I had a flare of green fire and quite a lot of white smoke. I was glad to have the respirator. I went upwind and let it heat for another

few minutes, then poured it into my steel muffin tray mold. As it turns out, this was not a great choice of mold. In one spot, the brass fused to the

steel and it took a hell of a lot of effort and the destruction of that one muffin cup to pry it out of there. After I wrenched it free, I wire

brushed the surface a bit to see the color.

Here's the brass compared to wire brushed pure copper for comparison:

As you can see, it's much more red than it should be. That's certainly due to a lot more zinc boiling off than I expected. Getting there though!

Next step will be to remelt this ingot and add another piece of zinc. This time I'll try sprinkling the charcoal over the molten alloy rather than at

the beginning. I'm not sure if it would be a good idea to try pushing the zinc under the copper's surface to encourage absorption - it might just boil

and throw molten copper around. The Scientific American link recommends pre-heating the second metal, although that might be more trouble than it's

worth since the zinc would be molten to even come close to copper temperatures.

|

|

|

elementcollector1

International Hazard

Posts: 2689

Registered: 28-12-2011

Location: The Known Universe

Member Is Offline

Mood: Molten

|

|

From what I've seen, an alloy most closely resembling 23K gold (and used for that purpose as faux gold leaf) is 85% copper, 15% zinc.

I can also safely inform you that melting the zinc and dropping the copper in doesn't work very well either - the zinc either combusts anyway, or the

whole thing solidifies into a half-brass, half-component brick. I've often wondered about what fluxes might help keep things from burning at the

higher temperatures of molten copper, but haven't looked into it too thoroughly.

I do remember that when melting lead-tin alloys for a phase diagram lab back in university, we used quite a bit of graphite powder as a flux,

filling up nearly half the crucible as compared to the lead-tin barely filling the bottom. The lead-tin came out very shiny and silver after polishing

- no oxidation whatsoever.

Elements Collected:52/87

Latest Acquired: Cl

Next in Line: Nd

|

|

|

Fulmen

International Hazard

Posts: 1729

Registered: 24-9-2005

Member Is Offline

Mood: Bored

|

|

I don't see why adding Cu to Zn shouldn't work. You would add the Cu in small portions, allowing it to dissolve as you gradually increase the

temperature. I'm guessing that the reason it's not done this way in the industry is that it would take more time. They also have the advantage of

chemical analysis to dial in the composition. The other downside to working slow would be increased time for oxidation, so it's not clear if it would

save more Zn unless a shielding is employed.

As for shielding I would try either carbon or perhaps boric acid?

We're not banging rocks together here. We know how to put a man back together.

|

|

|

bobm4360

Hazard to Self

Posts: 60

Registered: 18-4-2011

Location: On a wretched little island.

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Use borax as a flux. It concentrates the oxides into dross floating on the melt, and protects the melt from further oxidation.

|

|

|

MrHomeScientist

International Hazard

Posts: 1806

Registered: 24-10-2010

Location: Flerovium

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

When should the flux be added? Before or after melting? How much flux per melt? I assume it needs to be anhydrous borax, not the off-the-shelf

decahydrate? I have little experience with this.

I didn't have any noticeable oxides for this particular melt, so a cover flux might be more appropriate than a drossing flux in this case (if I

understand all that correctly).

Quote: Originally posted by Fulmen  | | I don't see why adding Cu to Zn shouldn't work. You would add the Cu in small portions, allowing it to dissolve as you gradually increase the

temperature. |

But brass' melting point is still quite a ways above zinc's boiling point, and below copper's melting point. I just don't see how that would work,

since the copper wouldn't melt. Plus if brass did form I imagine it would solidify at those temperatures. Unless copper has a high solubility in zinc.

This information has to be around somewhere; brass has certainly been around long enough.

|

|

|

aga

Forum Drunkard

Posts: 7030

Registered: 25-3-2014

Member Is Offline

|

|

When to add flux is a very contentious issue, which means that nobody knows for sure.

Add some before, during or after the melt, or two of those, or all three.

A few experiments and you'll know which works best.

Unfortunately the purity of your metals and the flux won't make it an inarguable set of experimental data.

|

|

|

Fulmen

International Hazard

Posts: 1729

Registered: 24-9-2005

Member Is Offline

Mood: Bored

|

|

I would expect copper to be soluble in molten zinc, at least when it's getting closer to the boiling point. As the copper dissolves the melting point

increases, so you would have to gradually ramp the heat as you add more copper.

As to when you should add the flux IDK, but I would use some from the start. Borax (sodium tetraborate, not the same as boric acid) could also work, I

expect the water would be driven off before the zinc melts.

We're not banging rocks together here. We know how to put a man back together.

|

|

|

elementcollector1

International Hazard

Posts: 2689

Registered: 28-12-2011

Location: The Known Universe

Member Is Offline

Mood: Molten

|

|

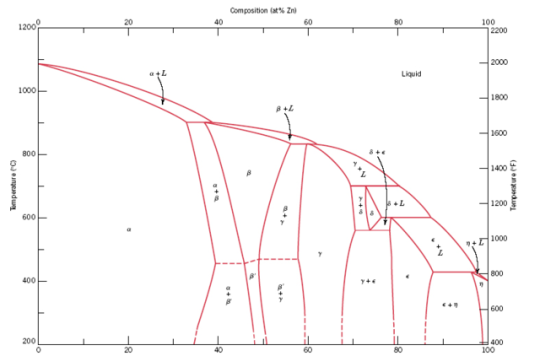

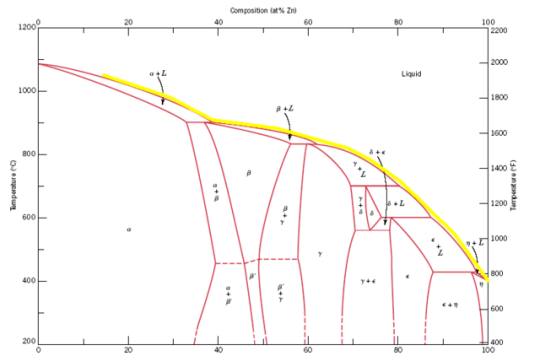

We can get an idea of how soluble the different metals are from the phase diagram. Thankfully, the Cu-Zn phase diagram is one of the best-studied

ones, so it's easy to find:

On the right is pure, 100% Zn, on the left is 0% Zn (or 100% Cu), and in the middle we have various solid and liquid phases. The two Pinchbeck brass

alloys fall right about here (in cyan and green, respectively, and the red line is the 85% alloy I suggested earlier):

Visually, the green line would appear to be the 'reddest' alloy, probably close to what MrHomeScientist's final product was if not even closer to

copper's appearance. The red line, on the other hand, would result in a much richer 'yellow' appearance, and the cyan would be somewhere in between.

Pinchbeck brasses are made to most closely resemble 18K gold (the most popular alloy of gold used in jewelry at the time of invention), whereas the

stuff I found is made to resemble 23K gold.

The only major chemical difference between these three alloys is the gap between them being in the completely liquid L phase and the completely solid

α phase. At this end of the phase diagram, you can see that zinc is very soluble in molten copper, judging from the massive α phase space

that takes up most of the left half. But, looking at the right half, you can also see that copper is comparatively not very soluble at all in molten

zinc - just a tiny little sliver of a η phase.

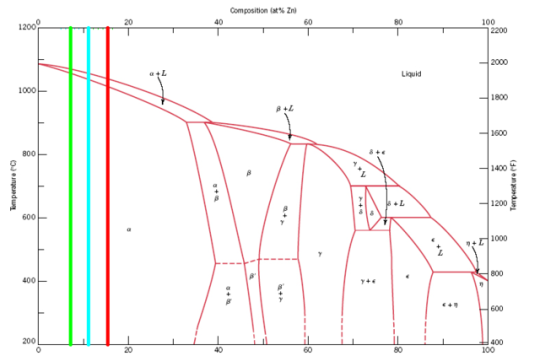

Were you to hold the whole thing at about the melting point of zinc (420 degrees C, rounded slightly for convenience) to avoid boiling, and add solid

copper, the phase composition would move in a horizontal line leftwards like so:

As you can see, what little copper that would manage to dissolve in the molten zinc would immediately solidify it into the η phase, and none would

diffuse much further due to the contents of your crucible now being a solid block. To avoid this, and keep everything liquid even after the copper and

zinc had mixed, you'd have to raise the temperature to about the melting point of each alloy in turn, which that far over in the phase diagram is

pretty close to the melting point of copper (about 1065, 1050 and 1035 degrees C for the green, cyan and red lines respectively, compared to pure

copper's 1085 C). The boiling point of zinc is about 907 C, so this approach just plain doesn't work.

The main sticking point, for me at least when I tried this, was that no matter what I did, the zinc would melt, float on top of the molten copper, and

then combust, coating the entire furnace in fluffy, yellow zinc oxide. What zinc did manage to diffuse into the copper created a brass of a very rich

golden hue, but I've no idea of the composition, only that it was probably a great deal more copper-rich than 85%. Pure gold actually isn't quite that

tint of yellow, but I liked how it turned out regardless.

I would imagine the best possible approach for adding flux would be to start off with a lot and then keep adding it. Borax might work, being a good

deal less dense than brass, copper or even zinc at 1.73 g/cc. It would melt, float above the molten metals, and exclude oxygen by forming a liquid

barrier that oxygen would take a while to diffuse through. We used graphite in my lab in more of a 'sacrificial' nature, where any oxygen that did

permeate the solid powder would react at the elevated temperatures to form minute amounts of gaseous carbon dioxide or monoxide.

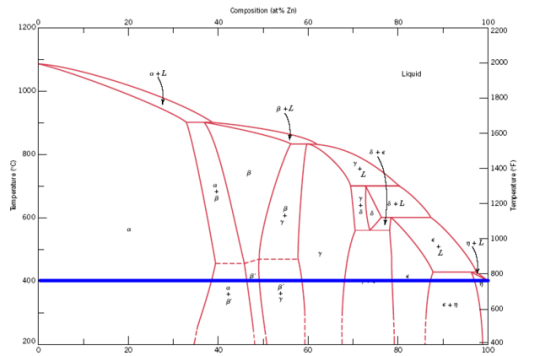

You could, in theory, add copper to zinc and ramp the temperature up so that everything stayed just barely liquid, following the liquidus

curve like this:

It would take some pretty good furnace heating controls to do so, though, probably a PID algorithm at the very least. Overshoot or heat too fast, and

you might find your zinc or zinc-rich brass boiling anyway.

[Edited on 4/10/2018 by elementcollector1]

Elements Collected:52/87

Latest Acquired: Cl

Next in Line: Nd

|

|

|

bobm4360

Hazard to Self

Posts: 60

Registered: 18-4-2011

Location: On a wretched little island.

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

As to borax, the OTC "20 Mule Team" works fine. It's a good flux for most Cu-based alloys, just skim yor melt before you pour.

|

|

|

OldNubbins

Hazard to Others

Posts: 136

Registered: 2-2-2017

Location: CA

Member Is Offline

Mood: Comfortably Numb

|

|

If you are concerned about when to add zinc, this is my experience:

I have a soldering iron I do not take care of. The iron plating over the copper core wore away and zinc/tin in the solder steadily dissolved the

copper core. So it seems the copper will dissolve into zinc far before it's melt point.

Also, I was attempting to melt some copper scrap but the gas regulator was fixed and did not put out enough pressure so the furnace would not get hot

enough. I threw a handful of zinc pennies into the crucible and the entire lot melted within 30 seconds.

|

|

|

Fulmen

International Hazard

Posts: 1729

Registered: 24-9-2005

Member Is Offline

Mood: Bored

|

|

Elementcollector: I think you're exaggerating the problem. All one really has to do is to keep adding Cu to the Zn while heating. If too much is added

the alloy would solidify, if so just wait until it melts again and continue. Even a small amount of Cu should raise the alloys boiling point

significantly, so temperature control should become less critical with time.

We're not banging rocks together here. We know how to put a man back together.

|

|

|

elementcollector1

International Hazard

Posts: 2689

Registered: 28-12-2011

Location: The Known Universe

Member Is Offline

Mood: Molten

|

|

Maybe so - it depends on how quickly the copper dissolves into the molten zinc. I couldn't find the boiling points of any brass alloys, and I would

imagine the relationship between copper content and boiling point isn't linear, so I don't know whether the small amount of copper that would dissolve

in the beginning would be enough to pull the boiling point out of range.

Elements Collected:52/87

Latest Acquired: Cl

Next in Line: Nd

|

|

|

Fulmen

International Hazard

Posts: 1729

Registered: 24-9-2005

Member Is Offline

Mood: Bored

|

|

Even if Raoult's law doesn't apply it should serve as a reasonable guideline. At 600°C you should be able to dissolve 10m% Cu, and 30m% at 800°C.

Considering the boiling point of Cu that should raise the alloys vapor pressure considerably. Combined with a flux that should be enough to prevent

excessive loss due to boiling.

I know it's all theory, but I think it looks promising.

We're not banging rocks together here. We know how to put a man back together.

|

|

|

Fleaker

International Hazard

Posts: 1252

Registered: 19-6-2005

Member Is Offline

Mood: nucleophilic

|

|

I always added the Zn to the Cu when the Cu was molten, then poured it.

Neither flask nor beaker.

"Kid, you don't even know just what you don't know. "

--The Dark Lord Sauron

|

|

|

MrHomeScientist

International Hazard

Posts: 1806

Registered: 24-10-2010

Location: Flerovium

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

EC1, that's really great information! Thanks for taking the time to post all that. That supports my intuition nicely  I didn't realize Pinchbeck was made to resemble 18K; that's good to know. I didn't realize Pinchbeck was made to resemble 18K; that's good to know.

WRT fluxes, it sounds like people here don't have much experience with them. Or there's just so much info and so many conflicting ways to do it that

it might not matter all that much. I suppose it's time to experiment, then!

|

|

|

unionised

International Hazard

Posts: 5134

Registered: 1-11-2003

Location: UK

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

You can make toffee by

melting sugar (well above 100C) and adding water or

heating water sugar together.

As far as I know, confectioners only choose one of those options.

I'd need a good reason before I chose to make brass by the analogy of the "adding water to molten sugar" process.

|

|

|

MrHomeScientist

International Hazard

Posts: 1806

Registered: 24-10-2010

Location: Flerovium

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

From the SA article I linked:

| Quote: | | First, melt the least fusible of the metals (that requiring the highest temperature) of which the alloy is to be composed, and after it is fused, keep

up the heat until the metal acquires such a temperature as will bear the introduction of the other metals without instantaneous and sensible cooling.

After this, introduce the other metals in the order of their infusibility the most difficult to melt first. Whatever may be the proportions of the

metals, it is indispensable to melt the most refractory first, and especially when it is to be the principal base, such as copper in

all [brasses]. |

I ran across the same advice in a few other sources, too. It's not a great idea for toffee, but apparently it's the way to go for metals.

|

|

|

happyfooddance

National Hazard

Posts: 530

Registered: 9-11-2017

Location: Los Angeles, Ca.

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by unionised  | You can make toffee by

melting sugar (well above 100C) and adding water or

heating water sugar together.

As far as I know, confectioners only choose one of those options.

I'd need a good reason before I chose to make brass by the analogy of the "adding water to molten sugar" process. |

No, you need some proteins to make toffee, what you are describing sounds like "caramel".

IME one uses a bit of roux or straight butter to make toffee. It doesn't take much, and you are correct that the process is very similar to making

caramel.

[Edited on 4-12-2018 by happyfooddance]

|

|

|

Fulmen

International Hazard

Posts: 1729

Registered: 24-9-2005

Member Is Offline

Mood: Bored

|

|

I'm not one to dismiss practical knowledge out of hand, but I still would like to know why. I can imagine many good reasons for doing this large scale

where the goal is to speed up the process and minimize oxidation when little or no flux is employed. It doesn't automatically follow that it will be

the best method when working in small batches.

We're not banging rocks together here. We know how to put a man back together.

|

|

|

Fleaker

International Hazard

Posts: 1252

Registered: 19-6-2005

Member Is Offline

Mood: nucleophilic

|

|

Borax glass is usually used as a cover flux for cuprous, gold, silver alloys.

The borax stops a lot of the zinc fume.

Neither flask nor beaker.

"Kid, you don't even know just what you don't know. "

--The Dark Lord Sauron

|

|

|

MrHomeScientist

International Hazard

Posts: 1806

Registered: 24-10-2010

Location: Flerovium

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Is the borax added before or after melting? Before adding zinc? Should it be dehydrated first or just throw in OTC borax? Trying to nail down the

procedure before I try it this weekend.

|

|

|

elementcollector1

International Hazard

Posts: 2689

Registered: 28-12-2011

Location: The Known Universe

Member Is Offline

Mood: Molten

|

|

'Borax glass', from what I can find, refers to the anhydrous salt, which is typically dehydrated by melting. The anhydrous, vitreous version melts at

around 878 degrees C.

From what little I could find, the important thing is that the borax coats the surfaces of whatever metals you're attempting to melt. I'd imagine that

putting enough in to leave no free air gaps in the crucible (but not enough to increase the thermal mass dramatically) would be optimal.

EDIT: More than a few websites are saying to use the borax sparingly, as it doesn't take much to create a protective barrier. Not sure what this would

mean for any uncovered metal that oxidizes prior to melting, but presumably the borax would at the very least segregate that from the metal itself.

Also, I've been thinking about making brasses like this from pennies, mainly to get rid of a bunch of scrap pennies I have lying around. Lacking a

proper furnace at the moment, but I can do the calculations for the ratio of copper pennies to zinc pennies to get each alloy listed, within about a

0.1% error. Good for people who don't want to go to the trouble of getting pure copper and zinc for precise alloys.

Pinchbeck 1 (89% Cu, 11% Zn): 29 copper pennies : 2 zinc pennies

Pinchbeck 2 (93% Cu, 7% Zn): 45 copper pennies : 1 zinc pennies

Faux 23K (85% Cu, 15% Zn): 25 copper pennies : 3 zinc pennies

[Edited on 4/14/2018 by elementcollector1]

Elements Collected:52/87

Latest Acquired: Cl

Next in Line: Nd

|

|

|

VSEPR_VOID

National Hazard

Posts: 719

Registered: 1-9-2017

Member Is Offline

Mood: Fullerenes

|

|

You should create an entry for pinchbeck brass on the List of Chemicals and Materials Made by Sciencemadness.org Users: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1AoI2VA5L4bmFw2HwXS2OVYTV...

Within cells interlinked

Within cells interlinked

Within cells interlinked

|

|

|

elementcollector1

International Hazard

Posts: 2689

Registered: 28-12-2011

Location: The Known Universe

Member Is Offline

Mood: Molten

|

|

Going to try to make "Pinchbeck 1" and the 85/15 alloy tomorrow from a few pennies (scaled-down versions of the ratios above). Hoping that a pinch of

borax and a stone surface for melting will allow me to get nice shiny samples so I can post color comparisons to real gold and a few brass coins I

found laying around.

...Also hoping my butane microtorch doesn't vaporize the zinc right off the bat. Gentle heating and allowing plenty of time for each copper

dissolution should help...

Elements Collected:52/87

Latest Acquired: Cl

Next in Line: Nd

|

|

|

MrHomeScientist

International Hazard

Posts: 1806

Registered: 24-10-2010

Location: Flerovium

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Good luck, EC1! Alloying pennies together is a great idea. The consistent masses between pennies should make for easy alloying calculations. And maybe

being plated in copper will help keep the zinc from escaping.

===========================================

Today I did some brass experimentation, with good results. Unfortunately I had to cut it short due to running out of propane, but I was able to make 3

different brasses. I recorded some of it, and you can watch that here: https://youtu.be/40W6Pp7MCuY

It's not really a full quality video so I won't be posting it publicly, but hopefully it will help you guys understand what I did.

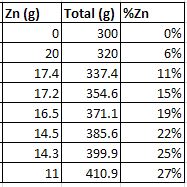

I started with 300g (well, 299.5g) of cut copper wire. I made several zinc buttons by gently melting with a propane torch and pouring into a round

ingot mold. I weighed each one, and wrote the mass in grams on them.

I also gave fluxing with borax a try, by adding some 20 Mule Team borax straight from the box directly to the hot crucible. This went much better than

I expected - since it's a decahydrate, I was sure I would get a lot of spattering and foaming from the water rapidly boiling off. Instead, it just

melted very calmly and easily. Nice! I added some right at the beginning, before the copper had melted, and added a bit more occasionally during the

process (see the video).

After the copper was molten, I would add one zinc button, stir with a graphite rod, then pour out a sample ingot. Then I'd return the crucible to the

furnace, let it heat up again, add another button, stir, and pour a sample. Here are my composition calculations, starting with 300g copper and

assuming all the zinc went into solution. Obviously I had a lot of zinc boil off, so that would lower the percentages. This also doesn't account for

the mass of the sample ingots removed, so that would raise the percentages. So the real value is probably +/- a few percent.

I made it to 3 sample ingots before my propane ran out. Here are the results, just after cooling and then after grinding and wire brushing:

The blob on the left you might recognize as the pure copper from my last post, for reference.

I'm thinking maybe 2 or 3 more zinc additions will get me to my target color. This is tons of fun

[Edited on 4-15-2018 by MrHomeScientist]

|

|

|

| Pages:

1

2

3 |