| Pages:

1

2 |

Assured Fish

Hazard to Others

Posts: 319

Registered: 31-8-2015

Location: Noo Z Land

Member Is Offline

Mood: Misanthropic

|

|

Antimatter question

Ok so we have all been told that if you take a particle and its corresponding anti particle and collide them together they both annihilate each other

producing 100% energy.

But this confuses me, energy is a property of matter, you cannot have energy without matter.

If you placed an electron and a positron inside a vessel without any other particles present and then both particles collided, what type of energy

would be created?

Photons seems odd because they are a type of matter and likely have an antimatter counterpart, as would any other fermions. Do bosons have anti

particles?

According to the laws of conservation of energy matter can neither be created nor destroyed, right?

|

|

|

LearnedAmateur

National Hazard

Posts: 513

Registered: 30-3-2017

Location: Somewhere in the UK

Member Is Offline

Mood: Free Radical

|

|

Energy is released as gamma radiation, two photons travelling in opposing directions to satisfy the conservation of momentum. The wavelength of each

photon is equal and proportional to the total energy (rest mass energy + kinetic energy, the latter of which may be negligible in comparison) of each

particle. There's nothing odd about the idea of photons being released - sure, they do have particle properties but the bit that matters (pardon the

pun) is the fact that they have neutral charge. I.E, the antimatter counterpart of a photon is, well, the photon. Also, the conservation of energy

refers to that alone - matter is a form of energy and it is well documented that certain processes (such as pair production and nuclear fusion)

readily convert one to the other. You can create and destroy matter but energy can only be converted to other forms. Hope that helps and I'll be happy

to answer any other questions.

[Edited on 17-10-2017 by LearnedAmateur]

In chemistry, sometimes the solution is the problem.

It’s been a while, but I’m not dead! Updated 7/1/2020. Shout out to Aga, we got along well.

|

|

|

wg48

National Hazard

Posts: 821

Registered: 21-11-2015

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Here is more info for the OP its a good detailed explanation of partcle/anitpartcle annihilation. It goes into detail about mass and energy which is

an important concept to understand in this subject.

https://profmattstrassler.com/articles-and-posts/particle-ph...

|

|

|

j_sum1

Administrator

Posts: 6338

Registered: 4-10-2014

Location: At home

Member Is Offline

Mood: Most of the ducks are in a row

|

|

I have been enjoying Dr Don Lincoln on these kinds of questions.

https://www.youtube.com/user/fermilab/videos

He does not answer your exact question but he does give a good primer on antimatter in these two vids.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=en2S1tBl1_s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qS7ueguKp14

|

|

|

DraconicAcid

International Hazard

Posts: 4360

Registered: 1-2-2013

Location: The tiniest college campus ever....

Member Is Online

Mood: Semi-victorious.

|

|

Photons are a form of energy, and since they have no mass, they are not matter.

Please remember: "Filtrate" is not a verb.

Write up your lab reports the way your instructor wants them, not the way your ex-instructor wants them.

|

|

|

Melgar

Anti-Spam Agent

Posts: 2004

Registered: 23-2-2010

Location: Connecticut

Member Is Offline

Mood: Estrified

|

|

Photons are not matter since they have no mass. Mass requires energy to accelerate, but for photons that are massless, they're traveling at the

maximum velocity that's possible in this universe no matter how much or little energy they contain.

The first step in the process of learning something is admitting that you don't know it already.

I'm givin' the spam shields max power at full warp, but they just dinna have the power! We're gonna have to evacuate to new forum software!

|

|

|

SWIM

National Hazard

Posts: 970

Registered: 3-9-2017

Member Is Offline

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by LearnedAmateur  | There's nothing odd about the idea of photons being released - sure, they do have particle properties but the bit that matters (pardon the pun) is the

fact that they have neutral charge. I.E, the antimatter counterpart of a photon is, well, the photon. Also, the conservation of energy refers to that

alone - matter is a form of energy and it is well documented that certain processes (such as pair production and nuclear fusion) readily convert one

to the other. You can create and destroy matter but energy can only be converted to other forms. Hope that helps and I'll be happy to answer any other

questions.

[Edited on 17-10-2017 by LearnedAmateur] |

Actually, I've got one. If it's the charge that matters then what about neutrons and neutrinos?

My knowledge of this is very sketchy, but I thought they were both matter.

|

|

|

Texium

Administrator

Posts: 4623

Registered: 11-1-2014

Location: Salt Lake City

Member Is Online

Mood: PhD candidate!

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by SWIM  | Actually, I've got one. If it's the charge that matters then what about neutrons and neutrinos?

My knowledge of this is very sketchy, but I thought they were both matter |

Isn't a neutron essentially a

proton with an embedded electron, hence its very slightly larger mass?

|

|

|

j_sum1

Administrator

Posts: 6338

Registered: 4-10-2014

Location: At home

Member Is Offline

Mood: Most of the ducks are in a row

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by zts16  | Quote: Originally posted by SWIM  | Actually, I've got one. If it's the charge that matters then what about neutrons and neutrinos?

My knowledge of this is very sketchy, but I thought they were both matter |

Isn't a neutron essentially a

proton with an embedded electron, hence its very slightly larger mass? |

Close.

A neutron can decay into a proton and an electron with the release of some energy and the loss of a little of the total mass.

In what form the energy is...? I forget.

|

|

|

Texium

Administrator

Posts: 4623

Registered: 11-1-2014

Location: Salt Lake City

Member Is Online

Mood: PhD candidate!

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by j_sum1  | Quote: Originally posted by zts16  | Quote: Originally posted by SWIM  | Actually, I've got one. If it's the charge that matters then what about neutrons and neutrinos?

My knowledge of this is very sketchy, but I thought they were both matter |

Isn't a neutron essentially a

proton with an embedded electron, hence its very slightly larger mass? |

Close.

A neutron can decay into a proton and an electron with the release of some energy and the loss of a little of the total mass.

In what form the energy is...? I forget. |

Ah, right, beta minus decay... seems strange and counterintuitive

too that it can go the other way, with a proton decaying into a neutron with the emission of a positron.

My current knowledge is limited to what I remember from AP Chemistry in high school. I'll probably get a rigorous schooling in this subject next

semester in Physical Chemistry II.

|

|

|

DraconicAcid

International Hazard

Posts: 4360

Registered: 1-2-2013

Location: The tiniest college campus ever....

Member Is Online

Mood: Semi-victorious.

|

|

I believe (but don't cite me) that a neutron will only undergo beta decay when it's in the nucleus of an atom that has too many neutrons, and the

increased nuclear binding energy makes up for the fact that ordinarily a neutron is more stable (and less massive) than a proton and electron. Nuclei

with too few neutrons can undergo beta capture, taking an electron from an inner orbital to turn a proton into a neutron, and I think the same process

happens in neutron stars. And planet killers made of pure neutronium.

Please remember: "Filtrate" is not a verb.

Write up your lab reports the way your instructor wants them, not the way your ex-instructor wants them.

|

|

|

LearnedAmateur

National Hazard

Posts: 513

Registered: 30-3-2017

Location: Somewhere in the UK

Member Is Offline

Mood: Free Radical

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by SWIM  |

Actually, I've got one. If it's the charge that matters then what about neutrons and neutrinos?

My knowledge of this is very sketchy, but I thought they were both matter. |

Charge is just one factor, others like spin can be opposite in matter-antimatter pairs but it really depends on what class of subatomic particle

you're discussing. I can't comment for neutrinos because their properties are above my knowledge but neutrons have an antimatter pair because their

constituent quarks (udd) have antimatter counterparts with opposite charge.

In chemistry, sometimes the solution is the problem.

It’s been a while, but I’m not dead! Updated 7/1/2020. Shout out to Aga, we got along well.

|

|

|

saphireblue

Harmless

Posts: 8

Registered: 14-9-2016

Member Is Offline

Mood: I am like Earth, mostly harmless

|

|

"Photons are a form of energy, and since they have no mass, they are not matter."

How is this possible?

1. " two photons travelling in opposing directions to satisfy the conservation of momentum" -> surely mass is also required to conserve momentum?

2. Photos can and do exert force (think of those black and white weather vane things in vacuum bulbs, or more recent experiments of "tractor" beams of

photons acting on individual atoms, pushing space sail ships with solar/laser light, etc). The classic expression for this is surely FORCE = MASS x

ACCELERATION.

(Please excuse my ignorance on this subject, but have always found it interesting... even though after 15 years of pondering I still can't wrap my

mind around the 2 slit experiment or particle vs. wave thing)

|

|

|

Assured Fish

Hazard to Others

Posts: 319

Registered: 31-8-2015

Location: Noo Z Land

Member Is Offline

Mood: Misanthropic

|

|

Ok my mind is a little bit blown. Ok my mind is a little bit blown.

Suddenly the universe is starting to make sense.

So the actual products of the collision is very dependent on the amount of energy put in. The way i worded my question is that both particles had no

momentum and so they would loose all their mass to form momentum energy, if we give the positron and electron momentum then we could make conceivably

larger particles.

But then theoretically if we were to give the electron and positron the same momentum as the mass energy of a positron and electron then we could

basically cancel the reaction but still have the collision take place. thus the positron and electron would just collide and then fly apart again

without annihilating each other conserving both momentum and mass but is this possible?

Also what they do at the LHC makes more sense now, they are not just smashing particles together, they are smashing particles and anti particles

together, really big and heavy particles and anti particles at insane speeds, or maybe just moderately heavy particles at even more insane speeds

since as we get closer to the speed of light the mass of the particles is increased until its infinite at the speed of light.

What particles and anti particles did they collide together to get the higgs then and at what speeds? I must research this.

|

|

|

wg48

National Hazard

Posts: 821

Registered: 21-11-2015

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Briefly correcting what seems to be some misconception of the most recent posts.

The rest mass of a neutron is greater than the rest mass of a proton and greater than the total rest mass of a proton plus the rest mass of an

electron. Neutrons are not stable out side of a nucleus. Protons are stable outside of a nucleus. Their stability inside a nucleus is dependent on

them having or not a decay path available (the short version).

Neutrons are not considered to contain electrons. They only contain quarks and gluons and I would guess/speculate photons (quarks are charged)

Photons have no rest mass but they do have mass/energy, momentum, and spin. Yes how can something have momentum with no rest mass? The short reply is

well photons do. Its tied up with the way we think about momentum in the low velocity (< < c) cases and the simplifications made when we first

learn about momentum and mass(rest).

I don’t know if an electron and a positron can bounce of each other but if they do its not because their momentum cancel. If their momentum cancel

it just means that the total momentum of the products must be zero ie the momentum of particles going one way is equal to the total momentum of

the particle going the opposite way so the total is zero. Momentum and mass/energy are always conserved.

I think all this is explained in the link I gave in my first post in this thread.

PS: thinking about, yes an electron and a positron can appear to bounce of each other because just as their energy/mass can convert to other

particles it could convert back in to an electron and a positron. Note: if sufficient energy/mass available they can convert into a shower of various

particles.

[Edited on 18-10-2017 by wg48]

|

|

|

LearnedAmateur

National Hazard

Posts: 513

Registered: 30-3-2017

Location: Somewhere in the UK

Member Is Offline

Mood: Free Radical

|

|

Momentum is more of a vector concept here, not so much the transformation of mass-energy. When a hypothetical object is stationary, it'll have zero

velocity thus zero momentum. Suddenly, it emits two particles travelling in opposite directions with equal velocity, say +2 and -2 units per second

along a single plane. These particles, both with identical mass and/or energy, must then have the same but opposite momenta - if you look at the maths

behind it, 2 + (-2) equals zero, therefore momentum is ultimately conserved. A lot of things work this way and it isn't readily apparent from the

surface, like two cars colliding head on to create a stationary wreck, an explosive detonating, even jumping will push the Earth a little bit but the

difference in mass is so huge that the velocity will basically be zero.

Back to the annihilation, the products will always be electromagnetic radiation but it is expected to be gamma due to the amount of energy produced

(c^2 is one helluva number). Increasing the kinetic energy/momentum of the particles will only serve to make the photons more energetic - this extra

energy has to go somewhere after all, so it becomes part of the only products. The only way you can generate an electron-positron pair is by passing

high energy gamma rays near an atomic nucleus, so annihilation itself is an irreversible reaction. BUT, if you had large atoms nearby to a high

kinetic energy (close to the speed of light) annhilation, then you can form another pair with just one of the produced photons if it has an energy at

least that of both the antiparticles. Mass isn't a property that needs to be conserved but energy is, so that's why antimatter pairs can form photons

- since momentum equals mass times velocity, it is correct to assume that the mass can be substituted by a form of energy, E=mc^2, giving the ultimate

equation p = (E*v)/(c^2). We then use this to describe the photon's momentum, simplifying the equation to p = E/c, since v now equals c.

[Edited on 18-10-2017 by LearnedAmateur]

In chemistry, sometimes the solution is the problem.

It’s been a while, but I’m not dead! Updated 7/1/2020. Shout out to Aga, we got along well.

|

|

|

Melgar

Anti-Spam Agent

Posts: 2004

Registered: 23-2-2010

Location: Connecticut

Member Is Offline

Mood: Estrified

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by saphireblue  | | 2. Photos can and do exert force (think of those black and white weather vane things in vacuum bulbs, or more recent experiments of "tractor" beams of

photons acting on individual atoms, pushing space sail ships with solar/laser light, etc). The classic expression for this is surely FORCE = MASS x

ACCELERATION. |

Radiometers are actually a bit sneaky in the way they work. They actually don't work at all if the bulb has a total vacuum in it. They need a

low-pressure gas to work. What happens is, the dark sides of the vanes absorb energy faster than the white ones. Gas molecules hit the vanes, absorb

some of their energy, then bounce away with most of that energy converted to kinetic energy. With all these molecules hitting the dark side at a low

velocity and ricocheting off of it with a higher velocity, some momentum is imparted to the vane, and obviously this effect would be larger on the

darker side.

A few weird aspects of physics that it took me some time to wrap my head around:

1) Cosmic microwave background radiation. This radiation dates back the Big Bang, and corresponds to black-body electromagnetic radiation. For the

first few micro/nano/pico/whatever seconds, the universe was too dense for photons to form, since they'd just immediately get absorbed by matter. At

around a temperature of 3000K, matter was spread out enough that photons could form, and did simultaneously throughout the universe (which wasn't very

large at the time). Now what always threw me off is the fact that even though nothing can travel faster than the speed of light, the universe can and

does EXPAND faster than the speed of light. It's a good thing too, otherwise it would have had an event horizon that it couldn't have escaped. So

the universe expanded faster than the photons could catch up to it, and those photons have been traveling outward from every point in the universe

since then. As the universe stretched, the photons' wavelengths have stretched too, to the point where they're now corresponding to a temperature of

about 2K. This means their energy is very, very low.

2) Particle wave duality makes a lot more sense if you imagine that the photon has to stop behaving like a wave and start behaving like a particle

when it stops moving or slows to matter's speed. What happens when this slowdown takes place? Well, that's what quantum mechanics is all about!

The first step in the process of learning something is admitting that you don't know it already.

I'm givin' the spam shields max power at full warp, but they just dinna have the power! We're gonna have to evacuate to new forum software!

|

|

|

LearnedAmateur

National Hazard

Posts: 513

Registered: 30-3-2017

Location: Somewhere in the UK

Member Is Offline

Mood: Free Radical

|

|

Can anyone offer any reasonable explanations as to why light is influenced by gravity despite being massless? Not only do black holes have event

horizons which represent the point where gravitational potential equals the speed of light, but massive objects are also able to bend light as

gravitational lenses outside of the EH if one is present. I'm guessing this has something to do with the curvature of space time associated with

gravity but is there actually a more logical, mechanical explanation?

In chemistry, sometimes the solution is the problem.

It’s been a while, but I’m not dead! Updated 7/1/2020. Shout out to Aga, we got along well.

|

|

|

wg48

National Hazard

Posts: 821

Registered: 21-11-2015

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by LearnedAmateur  | | Can anyone offer any reasonable explanations as to why light is influenced by gravity despite being massless? Not only do black holes have event

horizons which represent the point where gravitational potential equals the speed of light, but massive objects are also able to bend light as

gravitational lenses outside of the EH if one is present. I'm guessing this has something to do with the curvature of space time associated with

gravity but is there actually a more logical, mechanical explanation? |

Light has no rest mass but it does have mass/energy.

Irrespective of light having rest mass or not or aything else, it along with all other particles and objects not subject to a force (not gravity) move

along geodesics (straight lines in space time).

So yes it’s the curvature of space.

|

|

|

wg48

National Hazard

Posts: 821

Registered: 21-11-2015

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by Melgar  |

A few weird aspects of physics that it took me some time to wrap my head around:

Now what always threw me off is the fact that even though nothing can travel faster than the speed of light, the universe can and does EXPAND faster

than the speed of light. It's a good thing too, otherwise it would have had an event horizon that it couldn't have escaped. So the universe expanded

faster than the photons could catch up to it, and those photons have been traveling outward from every point in the universe since then. As the

universe stretched, the photons' wavelengths have stretched too, to the point where they're now corresponding to a temperature of about 2K. This

means their energy is very, very low.

|

That’s a common myth perpetuated by popular science writers and even by some people who should know better. Because of relativistic effects you

cannot just add up (the normal everyday low velocity way) the velocities between galaxies in a given line of sight to arrive at the velocity of a

distant galaxy.

To get the correct velocity the relativistic addition of velocities called Einstein velocity addition (google it for details) must be used. In which

case the final velocity can never exceed c.

Simply put there are no galaxies, not even the microwave background (surface of last scattering), receding away from us faster than the speed of

light.

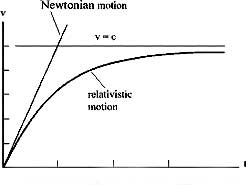

Below is a graphic of how the velocity varies with distance. The horizontal axis is distance. Its is assumed that on average the universe is isotropic

meaning that on average each galaxy is receding from its neighbour by a fixed velocity. The line marked Newtonian motion plots the velocity of a

galaxies with distance, a simple proportionality. The further they are away the faster they are receding, It must exceed c at some distance that’s

the myth.

The plot marked relativistic motion is correctly calculated and can never exceed c.

Edited: to improve the explanation

[Edited on 18-10-2017 by wg48]

[Edited on 18-10-2017 by wg48]

|

|

|

Melgar

Anti-Spam Agent

Posts: 2004

Registered: 23-2-2010

Location: Connecticut

Member Is Offline

Mood: Estrified

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by LearnedAmateur  | | Can anyone offer any reasonable explanations as to why light is influenced by gravity despite being massless? Not only do black holes have event

horizons which represent the point where gravitational potential equals the speed of light, but massive objects are also able to bend light as

gravitational lenses outside of the EH if one is present. I'm guessing this has something to do with the curvature of space time associated with

gravity but is there actually a more logical, mechanical explanation? |

Although people often assume that Einstein's Theory of Relativity is the "special" one, there are actually two of them: general relativity and special

relativity. General relativity covers scenarios at more ordinary velocities, and predicts that one consequence of gravity bending space-time is that

there should be no observable difference between an acceleration due to gravity and an acceleration due to accelerating. Any phenomenon you'd see if

you were in a constantly-accelerating elevator, you should also see while under the effects of a gravitational field. So far, this has proven to be

true in every experiment that's been done.

The main problem with general relativity is that even though it's one of those near-perfect theories of nature, gravity doesn't tend to work nice with

the other fundamental forces and their quantum mechanics. At least not on paper, and not yet.

The first step in the process of learning something is admitting that you don't know it already.

I'm givin' the spam shields max power at full warp, but they just dinna have the power! We're gonna have to evacuate to new forum software!

|

|

|

Melgar

Anti-Spam Agent

Posts: 2004

Registered: 23-2-2010

Location: Connecticut

Member Is Offline

Mood: Estrified

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by wg48  | | That’s a common myth perpetuated by popular science writers and even by some people who should know better. Because of relativistic effects you

cannot just add up (the normal everyday low velocity way) the velocities between galaxies in a given line of sight to arrive at the velocity of a

distant galaxy. |

I've been trying in vain to figure out what part of my post this was a response to, and I honestly don't know. The CMB radiation obviously HAS been

"catching up" with us over time, or else we wouldn't be able to detect it. The strange thing about it though, is that we're still detecting that

radiation 13 billion years later, and it seems to be emanating from every point in the universe more or less simultaneously. Of course, any radiation

that would have originated less than 13 billion light years away would have passed us already, and that would have included any radiation originating

between us and any distant galaxies. But the universe is 100 billion light years across, despite being only 13 billion years old, which was the weird

part that I initially had trouble understanding. (I think I have a pretty good grasp of it now, though.)

What you're referencing seems to just be an answer to the common mistake of summing velocities without using the appropriate Lorentz transformations.

(ie https://xkcd.com/675/)

The first step in the process of learning something is admitting that you don't know it already.

I'm givin' the spam shields max power at full warp, but they just dinna have the power! We're gonna have to evacuate to new forum software!

|

|

|

JJay

International Hazard

Posts: 3440

Registered: 15-10-2015

Member Is Offline

|

|

You know, a rock actually falls faster than a feather in a vacuum due to the greater gravitational force exerted by the rock (if you're confused,

assume that the rock is the size of Jupiter).

I know absolutely nothing about relativity. I always had a hard time seeing how I would ever use anything beyond Newtonian physics.

|

|

|

wg48

National Hazard

Posts: 821

Registered: 21-11-2015

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by JJay  | You know, a rock actually falls faster than a feather in a vacuum due to the greater gravitational force exerted by the rock (if you're confused,

assume that the rock is the size of Jupiter).

. |

I like that

|

|

|

wg48

National Hazard

Posts: 821

Registered: 21-11-2015

Member Is Offline

Mood: No Mood

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by Melgar  | Quote: Originally posted by wg48  | | That’s a common myth perpetuated by popular science writers and even by some people who should know better. Because of relativistic effects you

cannot just add up (the normal everyday low velocity way) the velocities between galaxies in a given line of sight to arrive at the velocity of a

distant galaxy. |

I've been trying in vain to figure out what part of my post this was a response to, and I honestly don't know. The CMB radiation obviously HAS been

"catching up" with us over time, or else we wouldn't be able to detect it. The strange thing about it though, is that we're still detecting that

radiation 13 billion years later, and it seems to be emanating from every point in the universe more or less simultaneously. Of course, any radiation

that would have originated less than 13 billion light years away would have passed us already, and that would have included any radiation originating

between us and any distant galaxies. But the universe is 100 billion light years across, despite being only 13 billion years old, which was the weird

part that I initially had trouble understanding. (I think I have a pretty good grasp of it now, though.)

What you're referencing seems to just be an answer to the common mistake of summing velocities without using the appropriate Lorentz transformations.

(ie https://xkcd.com/675/) |

Ok ignoring your reference to a cartoon joke.

I perplexed, what then did you mean by your statement:

"the universe can and does EXPAND faster than the speed of light"

In particular what did you mean by "the universe" and "EXPAND" ?

|

|

|

| Pages:

1

2 |