Melgar

Anti-Spam Agent

Posts: 2004

Registered: 23-2-2010

Location: Connecticut

Member Is Offline

Mood: Estrified

|

|

Might anthropogenic climate change actually benefit humanity, overall?

I consider myself to be an environmentalist, but before that, I'd like to think of myself as a scientist. Meaning that when it comes to things like

global policies, facts should always be more important than feelings. So I actually went and read the 2013 IPCC report, which covers basically everything that we know about climate change. And surprise, surprise, it turns out that climate change

alarmists get just about everything wrong! Some people seem to believe that the 2004 movie The Day After Tomorrow was based on science, even

though one climate scientist described it as "creatively violating every known law of thermodynamics." But another climate scientist described the

movie as being so terrible that it prompted him to engage more with the public, so I guess it's not all bad.

Now, alarmists often phrase what they're saying in a way that's technically not lying, but is still very dishonest. For example, they'll say that if

the polar ice caps melt, the oceans would rise by 200 feet (70 meters). This is true, but fails to point out that Antarctica (which contains 90% of

the world's land ice) is so cold that the few degrees difference that anthropogenic climate change might make, wouldn't bring it above water's

freezing point or anywhere close, even in the worst-case-scenario models. The Greenland ice sheet will probably go, over the course of the next few

millennia, but it won't be missed. Sea levels will rise about 20 feet (7 meters) and stay there.

That brings me to my next point: sea levels are going to rise 20 feet! Oh no! Most of the world's cities are on the coast! They'll all be flooded!

Whatever shall we do? Oh right. We could always just do what the Netherlands did. Half of that country is below sea level, and they somehow seem to

be getting by. I'm pretty sure their standard of living is among the best in the world, actually. Here's a hint: pick a Dutch city and look at the

last three letters of its name. Or think of a slur for lesbians. It's really not that difficult, they did it centuries ago. And for those villages

on the coast that are too small to afford it, well, the reason that they're on the coast is because it's where the water stops. If the water stopped

further uphill, then that's where the village would be. Since sea level rise is on the order of millimeters per decade, it wouldn't be visible over

the course of the life of any single person, and the normal cycles of rebuilding after typhoons would probably make the movement imperceptible. And

for all that land that's being lost to the sea, well, did I mention that there's going to be a whole new small continent to explore? Also, as the sea

level rises, it pushes the atmosphere up slightly, making high-elevation regions a bit more habitable, so overall, habitat loss is at worst, net zero.

Incidentally, does anyone know what event geologists predict will make life on Earth impossible, and when that will happen? It's actually the end of

plate tectonic activity, in about a billion years. When Earth's tectonic plates stop moving, carbonate rock will no longer cycle through Earth's

mantle, and the CO2 emissions from volcanic activity will stop. Plants will use up all the CO2 in the air, it'll get buried in sediment, and

eventually carbon will stop circulating in the environment. Since life is carbon-based, that's a problem. Fortunately, humans are here to save the

day, and have been digging up carbon and putting it back into the environment! Now, not only have we made it so that our current interglacial period

will probably last indefinitely (ie, no upcoming ice age to worry about), but there's going to be a whole lot more life on this planet! They've

already shown that in semi-arid regions, carbon fertilization of the atmosphere has resulted in increased plant growth. Plants have to "spend" water

in order to get carbon. CO2 reduction via photosynthesis actually reduces carbonic acid, but that means exposing water to the air to allow them to

combine. This can be a problem in dry climates. However, if there's more carbon in the atmosphere, less water needs to be used to collect it, and so

plant growth is possible in drier regions. The major downsides of global warming are that weather will be more variable [originally I said "less

predictable"] due the the more turbulent atmosphere, and there will be more really hot days every year. The other problems are all either negligible

or very easily managed, because of how slowly they're happening.

I sort of brought this discussion over from another thread. Here was the response:

Do you realize how extremely high the bias is towards researching negative aspects to climate change than researching positive ones? You NEED to make

your research point towards climate change being entirely a bad thing (or at least as many negatives as positives) if you ever plan on getting any

more funding. If your research points in the opposite direction, you'll be written off as a shill of the fossil fuel extraction industry. That hardly

matters, because facts are facts, but my point is that all the money is going to researching the negative aspects, rather than the considerable

positive ones.

But I'll go back to your response. Different plants, and different strains of those plants, respond differently to changes in environmental

conditions. It's why genetic diversity is important, and has evolved to where it has. Sure, a lot of crops are monocultures, but the seed companies

have huge amounts of genetics that were painstakingly collected from all over the world, and I would expect that they'd pull out some of those old

seeds if and when environmental conditions changed enough that it warranted it. CO2 levels were 1000 ppm only a million years ago, so most life on

Earth would manage just fine, I think.

| Quote: | | You list two major downsides; I'm not sure what you mean by weather being less predictable, |

I meant "more variable", and changed my post here to reflect that. And yeah, I'm aware of the fact that it seems like a tautology saying "a downside

of climate change is more variable weather", but I meant it in the sense that the agricultural production of any given region will vary more. Some

years, the output might be much higher than before, other years it might be much lower. But this will vary region to region, and due to the increase

in carbon, the net agricultural output of the planet, overall, would increase. The solution to this problem? Countries will have to share with each

other more. That's pretty much it. And with globalization, we're already doing that

| Quote: | | but extreme heat is not good for plant growth (nor for humans, wildlife, or infrastructure). This is especially true when paired with drought, which

is a consequence of an accelerated hydrological cycle in a warming world; perversely, so is flooding, which is also less than optimal for plants.

Other impacts you’ve written off as negligible include increased wildfires, |

The increase from ordinary local weather cycles (ie, El Nino) would be far greater than the component from anthropogenic climate change.

| Quote: | | soil salination from rising sea level, |

Explained this one above. Sea level rise is the lowest priority on the list of problems, IMO.

This is from a different problem that humans caused, which is a much worse problem than climate change (in my opinion), that being the introduction of

pest species into ecosystems. Reason being, climate change is gradual and species can and do adapt. Introducing a species is immediate and can be

devastating.

| Quote: | | Thusfar, we’ve only been considering land plants, which is a little parochial given that most of the planet’s photosynthesis takes place in the

ocean. |

You'd think so, given its size, but that's actually not true. Terrestrial plants are actually the greater contributor, because they have better

access to nutrients and the atmosphere. To be fair, it's like 56% to 44%, but it's still a bit surprising.

From the Wikipedia page on primary production:

"Using satellite-derived estimates of the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) for terrestrial habitats and sea-surface chlorophyll for the

oceans, it is estimated that the total (photoautotrophic) primary production for the Earth was 104.9 Gt C yr−1.[22] Of this, 56.4 Gt C yr−1

(53.8%), was the product of terrestrial organisms, while the remaining 48.5 Gt C yr−1, was accounted for by oceanic production."

| Quote: | Ocean photosynthesizers are not generally carbon-limited (and certainly not water-limited); the limiting factor for their growth is often a

micronutrient (iron in particular; eg, http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v407/n6805/abs/407695a0...). Photosynthesizers tend to deplete these nutrients from the sunlit layer, and

they are replenished by upwelling from below. However, warmer oceans tend to stratify thermally, inhibiting upwelling and surface photosynthetic

growth with it (this is why tropical waters are so nice and clear: there isn’t much growing in them). In a warming world, these low-productivity

regions are expected to spread.

Another consideration is the chemical impact of dissolved CO2 on ocean life, called ocean acidification. What a falling pH will mean for

photosynthesizers specifically (especially non-calcifying ones) is not yet clear, but it’s expected to have severe impacts on much ocean life,

especially corals and coral reefs (which provide food and other ecosystem services to millions worldwide, including some of the poorest among us).

|

Ocean acidification is buffered by carbonate rock (which is where >90% of Earth's carbon is located), and in any case, its pH is around 8, making

it slightly basic. It's never expected to actually become acidic, as in having a pH below 7. There actually needs to be enough CO2 dissolved in the

oceans in order to allow calcium bicarbonate to form, otherwise marine plankton aren't able to use it for their shells and such.

Sorry if I omitted anything. This post was a bit exhausting to write, and I need to take a break from the internet.

edit: I think I mixed up a few numbers. CO2 levels were last higher than they were now a million years ago. That's not very long geologically. They

were 1000 ppm longer ago, but I can't remember how long ago, and my brain is fried from trying to remember where all the damn quote tags were supposed

to go, so I need to take a break, like now.

[Edited on 10/11/17 by Melgar]

The first step in the process of learning something is admitting that you don't know it already.

I'm givin' the spam shields max power at full warp, but they just dinna have the power! We're gonna have to evacuate to new forum software!

|

|

|

SWIM

National Hazard

Posts: 970

Registered: 3-9-2017

Member Is Offline

|

|

That line about the rising sea level pushing the atmosphere up really stuck in my craw till I thought about it, but I think I get it.

Although the total volume of H2O on earth would be reduced by the ice melting and contracting, the resulting water would end up at sea level instead

of high atop some plateau in Antarctica and would therefore displace a greater mass of air than it did before because of higher atmospheric density

down there.

Is that it?

|

|

|

Melgar

Anti-Spam Agent

Posts: 2004

Registered: 23-2-2010

Location: Connecticut

Member Is Offline

Mood: Estrified

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by SWIM  | That line about the rising sea level pushing the atmosphere up really stuck in my craw till I thought about it, but I think I get it.

Although the total volume of H2O on earth would be reduced by the ice melting and contracting, the resulting water would end up at sea level instead

of high atop some plateau in Antarctica and would therefore displace a greater mass of air than it did before because of higher atmospheric density

down there.

Is that it? |

That's one of the contributing factors. Another effect would be that warmer air and water expand, which would raise both sea levels and the habitable

elevation, which was taken into account when these figures were calculated.

A related issue is that even though you hear these alarmists freaking out about ice shelves breaking in Antarctica, sea ice doesn't matter at all when

it comes to sea levels rising. That ice is floating, meaning that it's displacing an amount of water exactly equal to its mass.

The first step in the process of learning something is admitting that you don't know it already.

I'm givin' the spam shields max power at full warp, but they just dinna have the power! We're gonna have to evacuate to new forum software!

|

|

|

mayko

International Hazard

Posts: 1218

Registered: 17-1-2013

Location: Carrboro, NC

Member Is Offline

Mood: anomalous (Euclid class)

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by Melgar  | | For example, they'll say that if the polar ice caps melt, the oceans would rise by 200 feet (70 meters). This is true, but fails to point out that

Antarctica (which contains 90% of the world's land ice) is so cold that the few degrees difference that anthropogenic climate change might make,

wouldn't bring it above water's freezing point or anywhere close, even in the worst-case-scenario models. |

Antarctic land ice won’t melt in place under any realistic scenario; you’re correct there. However, I am not aware of any serious commentator

claiming that it will. What Antarctic land ice does do is calve into the ocean, and then melt. (You earlier cited the IPCC AR5, which puts the current

sea level rise contribution from Antarctic ice at ~0.4 mm/year and rising ) This process is accelerated by warming ocean water.

It’s worth mentioning that, contrary to the coming claim that research is biased towards the alarmist, the GCM simulations used by the IPCC likely

underestimate sea level rise: http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/7/4/0440...

| Quote: | | Since sea level rise is on the order of millimeters per decade, it wouldn't be visible over the course of the life of any single person, and the

normal cycles of rebuilding after typhoons would probably make the movement imperceptible. And for all that land that's being lost to the sea, well,

did I mention that there's going to be a whole new small continent to explore? |

You’re lowballing the SLR rate by an order of magnitude; it’s currently clocking ~3.4 mm/year (http://sealevel.colorado.edu) and accelerating. That still may not sound like much, but it builds up, and it adds to things like storm surge. As

to the notion that future impact will be imperceptible, well, present impact can ALREADY be perceived. One example: coastal cities already face

‘nuisance flooding’, not during storms, but during especially high tides. This has been credibly attributed to rising sea levels (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2016EF000423/full ) Though the name may make the issue sound trivial, it’s not: Miami is shelling out

hundreds of millions of dollars to cope, with no end in sight.

| Quote: | | Also, as the sea level rises, it pushes the atmosphere up slightly, making high-elevation regions a bit more habitable, so overall, habitat loss is at

worst, net zero. |

Without more detail, I’m finding the claim of equal-or-better habitat exchange very difficult to believe; can you elaborate or provide a source?

| Quote: | | Do you realize how extremely high the bias is towards researching negative aspects to climate change than researching positive ones? You NEED to make

your research point towards climate change being entirely a bad thing (or at least as many negatives as positives) if you ever plan on getting any

more funding. If your research points in the opposite direction, you'll be written off as a shill of the fossil fuel extraction industry. That hardly

matters, because facts are facts, but my point is that all the money is going to researching the negative aspects, rather than the considerable

positive ones. |

This is the same excuse that creationists make for the lack of support for their position, and it could be reworded to defend ANY fringe perspective.

It’s not how academic funding works in general, and it’s not true that contrarian research can’t get funded. (The Idsos, for example, ain't exactly hurting for money ) . None of this is to say that funding bias has never occurred, ever, in the history of the world, but it does

beg the question, “Are there many legitimate positive results to be found in the first place?” I also have to wonder, did the earlier, more

optimistic, estimates of CO2 fertilization kill any researchers’ careers? Is there actually any evidence that research showing neutral or improved

pest responses has been suppressed? Without a reliable way to detect funding bias, these remarks are pretty nihilistic, and there’s not much I can

do with them.

| Quote: | | Quote: | | but extreme heat is not good for plant growth (nor for humans, wildlife, or infrastructure). This is especially true when paired with drought, which

is a consequence of an accelerated hydrological cycle in a warming world; perversely, so is flooding, which is also less than optimal for plants.

Other impacts you’ve written off as negligible include increased wildfires, |

The increase from ordinary local weather cycles (ie, El Nino) would be far greater than the component from anthropogenic climate change.

|

This assertion is too vague to comment on in much detail, other than to say:

1. Long-term increases in wildfire severity have been observed and credibly attributed to anthropogenic climate change (eg, http://www.pnas.org/content/113/42/11770.short ).

2. the El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is an oscillation, which makes it a questionable explanation for long-term trends. Additionally, because

ENSO is overlayed on a warming trend, strong El Ninos augment the base temperature, making it hotter than it would be with either process alone (Grant

Foster has some good discussions on the additive effects of internal variation and trend; you might start here or here

| Quote: |

This is from a different problem that humans caused, which is a much worse problem than climate change (in my opinion), that being the introduction of

pest species into ecosystems. Reason being, climate change is gradual and species can and do adapt. Introducing a species is immediate and can be

devastating. |

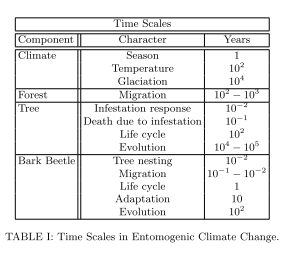

Bark beetles are native to North America; they are not an introduced pest (though introduced exotics certainly are a serious problem). As the linked

Forest Service article discusses, their outbreaks were few and far between until quite recently; the causes include hydrological stress in their host

plants and lower larval mortality due to milder winters.

As to the rate of anthropogenic climate change, it is geologically and evolutionarily abrupt. You are correct that organisms can adapt to a changing

environment, but they are not arbitrarily plastic. Moreover, adaptation doesn’t occur at the same rate in all species, which is a particular problem

for conifers faced with bark beetles: beetles can quickly adapt through range expansion, whereas forests can not

(source: csc.ucdavis.edu/~chaos/papers/ecc.pdf)

Additionally, the ghost forests left in the beetles’ wake are serious wildfire hazards.

| Quote: | | Quote: | | Thusfar, we’ve only been considering land plants, which is a little parochial given that most of the planet’s photosynthesis takes place in the

ocean. |

You'd think so, given its size, but that's actually not true. Terrestrial plants are actually the greater contributor, because they have better

access to nutrients and the atmosphere. To be fair, it's like 56% to 44%, but it's still a bit surprising. |

That is surprising; I will have to read some more into this but it appears I may have retained some middle-school textbook misinformation.

Nonetheless, ocean productivity is important and worth discussing.

| Quote: | | Ocean acidification is buffered by carbonate rock (which is where >90% of Earth's carbon is located), and in any case, its pH is around 8, making

it slightly basic. It's never expected to actually become acidic, as in having a pH below 7. There actually needs to be enough CO2 dissolved in the

oceans in order to allow calcium bicarbonate to form, otherwise marine plankton aren't able to use it for their shells and such.

|

It’s true that seawater is buffered by the carbonate system; however, the resistance to a pH change occurs by the reaction of carbonate with H+ to

from bicarbonate, thus depleting the carbonate ion. Carbonate ion is one of the factors controlling the saturation state of calcium carbonate

(essentially, its Ksp). It’s true that acidification will never be so severe that ocean pH drops below 7, but calcifification is most directly

impacted by the saturation state, not the pH. (There has been some research on the impact of pH changes themselves on some non-calcifying organisms,

but it’s been languishing in my to-read pile for months or more :/ )

One interesting aspect of seawater chemisty is that, on a long (millenia + ) time scale, carbonate saturation state is less dependent from CO2 and

mostly controlled by alkalinity (ie, Ca2+ concentration, the other half of the Ksp). On these long time scales, the system tends to be

self-regulating, since a high-CO2 world tends to have more and more acidic precipitation, with the consequence of increased weathering rates on land

and a greater flux of alkalinity to the ocean. This means that equilibrium states are possible in which saturation state is high in spite ofa low pH

(the carbonate capstones following snowball earth deglaciations are one example: ) You might think that this means that everything is OK in the

present, but remember, this only occurs under conditions of long-term equilibrium, whereas the carbon cycle is currently anything but. One (very good)

review puts it :

| Quote: | Thus, the presence of “carbonate

factories” with widespread CaCO3 production and burial is entirely consis-

tent with a high CO2, low pH world. In long-term quasi-steady-state condi-

tions, there is also sufficient time for evolutionary innovation and adaptation by the biota to low pH conditions. Only in significant and

geologically “rapid” departures from steady-state carbon cycling will both pH and saturation fall together, stressing calcifying marine organisms

at a rate that may be beyond their ability to adapt and evolve. It is these transient events, in which ocean chemistry may have been perturbed in

similar ways to the current “great geophysical experiment,” that we must look to for clues about future responses and biotic impacts.

|

Kump, L., Bralower, T., & Ridgwell, A. (2008). Ocean Acidification in Deep Time. Oceanography, 22(4), 94–107.

This also provides an example of why casual comparisons to past high-CO2 episodes in Earth’s history are often not informative.

| Quote: | | That brings me to my next point: sea levels are going to rise 20 feet! Oh no! Most of the world's cities are on the coast! They'll all be flooded!

Whatever shall we do? Oh right. We could always just do what the Netherlands did. Half of that country is below sea level, and they somehow seem to

be getting by. I'm pretty sure their standard of living is among the best in the world, actually. Here's a hint: pick a Dutch city and look at the

last three letters of its name. Or think of a slur for lesbians. It's really not that difficult, they did it centuries ago. And for those villages

on the coast that are too small to afford it, well, the reason that they're on the coast is because it's where the water stops. If the water stopped

further uphill, then that's where the village would be. |

As I mentioned, there are some steps that can be taken to mitigate these problems somewhat, however, they take money and political will that just

aren’t on the table. Maybe Miami could be kept afloat if we all rolled up our sleeves and built dikes around it. Is there any reason to believe

that’s going to happen? The legislature of my home state has infamously fought against considering evidence-based SLR projections in planning and development. Am I to expect meaningful mitigation steps from those clowns? The last line you wrote

is ominous: While an affluent nation like the Netherlands might be able to persist, are small island nations which lack funds (assuming mitigation is

possible in the first place) simply expected to accept annhiliation, for the good of “humanity as a whole”? (yes, apparently ) Who gets the mineral rights to their territory once it’s abandoned? I don’t know how these and other questions (What

worthwhile causes will go unfunded because resources are tied up building and maintaining levees around Boston?) can actually be addressed without

this becoming a dreaded Political Thread. (There are things here and in the recycling thread that I’m not going to comment on for this reason,

though believe me I have some Opinions).

| Quote: | | Sorry if I omitted anything. This post was a bit exhausting to write, and I need to take a break from the internet. |

I appreciate your effort; these are complex issues and making informed, good-faith posts takes time and work (and then when you're finally ready to

hit submit, you find the thread has been overrun with trolls and Detritus’d by mods, LOL!)

al-khemie is not a terrorist organization

"Chemicals, chemicals... I need chemicals!" - George Hayduke

"Wubbalubba dub-dub!" - Rick Sanchez

|

|

|

nitro-genes

International Hazard

Posts: 1048

Registered: 5-4-2005

Member Is Offline

|

|

Maybe one day we'll all say; "Hey, it's good that we put all that CO2 and methane in the air, or we would now be freezing our asses off"

Seriously though, what is the general consensus among climatologists regarding the cause and impact of climate change?

You guys seem much better informed about climate change than me, so maybe I'm missing the point here, but if there is one thing that bothers me with

climate change models is that (as with many models), it (to me) seems to be based on many assumptions and might be lacking important potential factors

that we don't understand yet. A commonly used argument is "If we can't accurately predict the weather, how can we predict climate change?" To which

the pro-climate change group will answer "Climate is much more predictable, because it happens on a much larger time scale". But when you google "What

causes an ice age?", nobody seems to have a clue. IIRC and depending on which model, average global temperatures may have been more than 11-20 deg C

apart over he cause of the earths history, so is the temperature rise after our industrial revolution (1.8 deg or so?) really causal and significantly

higher than can be expected from a glacial recovery? There is an obvious inherent problem with long term climate research and that is that all

important data, like global temperature, solar output, position, angle and distance of the earth from the sun, atmospheric composition (gasses/dust),

sea currents and level, plate tectonics and likely even biotic factors, are all based on indirect evidence, which inherently means based on

assumptions. There is only so many assumptions that can be made after which things stop to be scientific, let alone putting them into a predictive

model or determine causality. To make matters worse, complex interactions between all of these factors likely exist and may hardly be completely

understood yet. Carbon fertilization is one of these potential negative feedback loops that also occurred to me, likely there are many more that we

don't understand yet and not taken into the present day models. Really don't get these alarmist calls for artificial carbon fixation though,

intervening in a system that you don't completely understand seems downright stupid and potentially dangerous.

[Edited on 12-10-2017 by nitro-genes]

|

|

|

clearly_not_atara

International Hazard

Posts: 2789

Registered: 3-11-2013

Member Is Offline

Mood: Big

|

|

| Quote: | | Incidentally, does anyone know what event geologists predict will make life on Earth impossible, and when that will happen? It's actually the end of

plate tectonic activity, in about a billion years. When Earth's tectonic plates stop moving, carbonate rock will no longer cycle through Earth's

mantle, and the CO2 emissions from volcanic activity will stop. Plants will use up all the CO2 in the air, it'll get buried in sediment, and

eventually carbon will stop circulating in the environment. Since life is carbon-based, that's a problem. Fortunately, humans are here to save the

day, and have been digging up carbon and putting it back into the environment! Now, not only have we made it so that our current interglacial period

will probably last indefinitely (ie, no upcoming ice age to worry about), but there's going to be a whole lot more life on this planet! They've

already shown that in semi-arid regions, carbon fertilization of the atmosphere has resulted in increased plant growth. Plants have to "spend" water

in order to get carbon. CO2 reduction via photosynthesis actually reduces carbonic acid, but that means exposing water to the air to allow them to

combine. This can be a problem in dry climates. However, if there's more carbon in the atmosphere, less water needs to be used to collect it, and so

plant growth is possible in drier regions. The major downsides of global warming are that weather will be more variable [originally I said "less

predictable"] due the the more turbulent atmosphere, and there will be more really hot days every year. The other problems are all either negligible

or very easily managed, because of how slowly they're happening. |

As far as I understand it, this is inaccurate and in fact anthropogenic CO2 actually makes this problem worse.

CO2 is removed from the biosphere primarily by the (slow) reaction of CO2 with magnesium silicates. Magnesium silicates (olivine, talc, etc) are the

primary component of the Earth's mantle. The rate of CO2 sequestration is related to the rate of erosion of magnesium silicate rocks, which is related

to the quantity of precipitation and humidity in the atmosphere, which increases with warmer atmosphere due to increased evaporation from the ocean.

Higher temperatures lead to higher rates of sequestration, lower temperatures lead to lower rates, and the rate of release (by volcanic activity) is

roughly constant. During a warm period, the rate of weathering exceeds the rate of volcanic CO2 release; during a cold period, the opposite occurs. So

the Earth undergoes a periodic tectonic carbon oscillation between low-carbon periods -- also known as ice ages -- and high carbon periods, also known

as warm periods, also known as the present day.

Driving more carbon into the atmosphere during a warm period increases the rate of magnesium silicate erosion which increases the rate of carbon

sequestration. The result is a long-term net decrease of carbon in the biosphere which is reversed only by tectonic activity, because that

carbon generally is not released until the resulting MgCO3 sinks all the way to the mantle and flows out a volcano.

In the future, increases in solar luminosity will increase the temperature of the Earth and therefore also increase the rate of erosion of olivine

formations, decreasing the equilibrium concentration of CO2 in the biosphere. The result is that photosynthesis stops working.

The locking up of carbon as petrochemicals is really just a rounding error relative to the larger tectonic cycle, because the quantity of carbon in

the mantle vastly exceeds that available in the crust (because the mantle is 1000x larger than the crust!), so even magically returning all of the

petrochemical carbon to the mantle would have a trivial effect on carbon release by volcanism.

As such our release of petrochemical carbon does not prevent the long-term loss of carbon from the biosphere and may speed the arrival of a new

glaciation. To wit: bad.

In order to prevent this low-carbon future, a better solution would be to build a solar deflector in space, but that won't be necessary for another

few hundred million years, at which point, hopefully, the price of satellites will have decreased somewhat. Alternatively, we can just keep calcining

limestone and magnesite and making it into cement, which could probably shore up the carbon until the Sun gets way too hot for us to live here

anymore. This requires shitloads of input energy which means that we'd have to keep doing it for millions of years to really have an impact.

Also it really doesn't make sense for plate tectonics to end on a 500-million year timescale because the energy available for tectonics is driven

primarily by the decay of thorium-232 which has a half-life of 14 billion years (14000 million years) and as such the amount of thorium (and

corresponding available decay energy) would decrease by just 2.4% over the next 500 million years. I assume you heard that the world would run out of

carbon (which is true) and mistakenly filled in the blanks with "because tectonics". Which is close but not quite accurate.

[Edited on 12-10-2017 by clearly_not_atara]

|

|

|

aga

Forum Drunkard

Posts: 7030

Registered: 25-3-2014

Member Is Offline

|

|

Human activity on any scale worth mentioning is very very recent : comparable to a large asteroid strike that took a hundred years to impact, then

another hundred to explode, then another hundred years for the fallout to hit.

As far as this Planet is concerned, our activities may delay or advance it's own timetable, but nothing more.

As a species, we tend to think the Universe revolves around Us.

It does Not - 'things' continue along their own schedules regardless.

Whether we ever existed or not makes no long term difference to this Planet or Universe.

[Edited on 12-10-2017 by aga]

|

|

|

Melgar

Anti-Spam Agent

Posts: 2004

Registered: 23-2-2010

Location: Connecticut

Member Is Offline

Mood: Estrified

|

|

I guess I should explain myself better. To be clear, I'm not advocating that we all drive coal-burning Hummers until our fossil fuels run out or

anything. We need to stretch out our use of fossil fuels as long as we can, until we have some technology that can replace things like diesel

engines. We can replace coal-burning power plants with nuclear ones easily enough, and use renewable energy where it's available. Cargo ships and

even freight trains could be powered by nuclear reactors too. Cars already are running on battery power, but no battery can ever approach the energy

densities of diesel and turbofan engines. We can't run tractor trailers and airplanes on batteries, essentially. We should certainly cut back on

fossil fuel usage though, not so much because of climate change, but because we don't want to continue relying on fossil fuels until suddenly we find

ourselves without any.

Really, I think we should limit fossil fuel usage to only those things we have no replacements for. Things like ocean acidification are only a

problem if we raise CO2 levels too quickly. From my understanding, the ocean could absorb all the CO2 we could emit, but ocean currents aren't fast,

and if we dump all the CO2 in the water at the surface at once, then that water in particular could have problems. A more gradual increase, that

allowed natural cycles some time for adjustment, would eliminate a large part of the problem, even if we eventually did use up all our fossil fuels.

What I think is counterproductive are those so-called "clean coal" power plants, that waste a good fraction of their energy pumping their exhaust

gases back into natural gas wells or whatever. So we use up fossil fuels in a really inefficient way, when we could instead transition to

next-generation nuclear power if we weren't such cowards. Coal can be turned into hydrocarbons, and from there be used to fuel airplanes and heavy

machinery and such. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coal_liquefaction) We shouldn't be wasting it generating electricity, when we have so many other options.

Well, considering that humans are putting carbon into the environment that originated in continental plates, the fact that there's more overall carbon

circulating could actually make up for that. I got that information from the Wikipedia page "Timeline of the Far Future", and you seem to be mostly correct. This kind of assumes that evolution stops, which means it's probably not

accurate, but then it'd be impossible to predict what direction life will evolve anyway. However, you are not actually correct about plate tectonics,

since it's actually the increase in the sun's luminosity, leading to the oceans disappearing, that results in the end of plate tectonics. This

increase in luminosity would of course dwarf any effects caused by anthropogenic global warming. Of course, I wasn't entirely correct either, but a

billion years in the future is really too far ahead to even speculate on whether human-like life will even exist. It's perhaps more important to

forestall the next ice age though, which we are in fact doing.

Seeing as it's solar luminosity that's the problem, they've actually done feasibility studies on pumping SO2 into the upper atmosphere via

balloon-supported conduits. SO2 is then oxidized to SO3, which sucks up any water that comes near it, until it forms a tiny reflective droplet. The

acidity is insignificant, since it'd stay airborne for years. Volcanic eruptions have done the same thing in the past, resulting in cooler climates

for the next few years or so. It'd actually be extremely cheap and effective, and the consensus is that virtually any country on Earth could do it

alone.

| Quote: | | But when you google "What causes an ice age?", nobody seems to have a clue. |

I have a clue. The positions of continents, first and foremost. Earth cycles between Pangaea states and "a bunch of continents" states. It's done

this maybe three or four times now. Continents are made out of less-dense rock, which floats. But when all the continents are in the same place,

they insulate the magma underneath it, making it hotter. When it gets hotter, then that magma rises, creating a magma plume which then breaks up the

Pangaea continent again. Hence, plate tectonics. Anyway, continents get in the way of ocean currents and jet streams and such, and change Earth's

climate as they move around. The other issue is that plants have been getting more and more efficient at pulling carbon out of the atmosphere, and

have caused CO2 levels to drop from REALLY high during the Carboniferous period, to our record low, just before the Industrial Revolution.

One other effect that dwarfs a lot of these positive feedback loops that get much more attention is cloud albedo. A warmer planet has more

precipitation, and thus more clouds. And those clouds reflect sunlight, cooling it somewhat. Convenient, eh?

But isn't Antarctic land ice replenished by precipitation at roughly the same rate that glaciers calve into the ocean? And wouldn't that

precipitation increase if the Earth was warmer? I guess the glaciers would calve more, but it still seems like everything would cancel out, or come

very close to that.

I actually was surprised by the very scientific tone that the IPCC report took. For some reason I expected it to be more like Al Gore's movie. Also,

there was a lot of kerfuffle in the media about how Saudi Arabia got some graphs changed or something, and it seemed like there were a lot of

exaggerated scandals surrounding it, which is why I read it in the first place. And if I didn't remember everything exactly right, that's probably

because I read it when it came out, in 2013 or so.

| Quote: | | This is the same excuse that creationists make for the lack of support for their position, and it could be reworded to defend ANY fringe perspective.

It’s not how academic funding works in general, and it’s not true that contrarian research can’t get funded. |

I was kind of aware that I was treading in that direction, and so I'll rephrase my statement: Bad science is a lot easier to get published when it

points to AGW as a negative thing overall. Like those studies regarding crop nutrition. Don't you think that people would breed new crops that are

more nutritious if high CO2 levels altered the nutrient levels of current crops? Crop breeding is much faster than AGW, and genetic engineering much,

much faster than AGW.

I remember reading a published article about some zooplankton species, describing how ocean acidification would dissolve its shell right out from

under it! As though it had no ability to maintain homeostasis within its own body! Ocean pH levels vary plenty from place to place, and it's

ridiculous to assume that plankton are unable to deal with slight changes to pH.

Just to make sure everyone's aware, there was a huge ice sheet covering Canada only 10,000 years ago, stretching to the Great Lakes. Sea levels were

much lower, and there was that famous "Land Bridge" at the Bering Strait. Also, that necessarily means that coral reefs are all younger than 10,000

years old, since they would have grown as sea levels rose. I believe I read at one point that coral reefs are a temporary phenomenon that only exist

immediately following sea level rises. Eventually, they're knocked down by storms, below the photic zone, where they can't regrow.

Also, I might occasionally talk about "alarmists" or similar, but when I describe an idiot who dishonestly implies that global warming will be far

worse than it actually will be, I'm almost certainly talking about one loathsome alarmist in particular: Bill McKibben. He's certainly no scientist, and not much of a journalist, but he is nothing if not an alarmist. His first book on AGW

was titled "The End of Nature". Hyperbolic at all? His mantra seems to be "mankind has sinned against our mother earth, and we must repent by

reducing our energy consumption to pre-industrial levels!" While this sort of quasi-religious language is great for generating a large, misinformed

following, that's about all it's good for. The man seems to care more about being the center of attention than he cares about the future of humanity.

That is, he's a narcissist. I was ambivalent about the man (though still mostly disliking him) right up until he wrote an article titled "Fukushima

Proves that Nuclear Power is Unsafe". Now he's my sworn enemy. I met a guy who had actually tried to challenge him on some of his shitty math once,

and he affirmed that he's quite a dismissive dickhead in person too. He's been the source of a lot of these popular myths regarding AGW. But I guess

I should probably assume that the majority of people here don't buy into his nonsense, and so there's no need to argue against that idiot here.

And that's enough writing on this subject for today, now that I've gotten my antipathy towards Bill McKibben out of my system.

@mayko: There was a lot to your post, and I'll try and address the rest next chance I get.

edit: Stephen Colbert had a good bit with him. He asked him how he got to New York, and when it became clear he'd flown, he then asked him if he'd

gotten here in a dirigible powered by hypocrisy.

[Edited on 10/16/17 by Melgar]

The first step in the process of learning something is admitting that you don't know it already.

I'm givin' the spam shields max power at full warp, but they just dinna have the power! We're gonna have to evacuate to new forum software!

|

|

|

|