White Yeti - 21-6-2012 at 16:29

I was wondering how would one de-polymerise tannic acid into gallic acid monomers.

My ultimate goal is to make pyrogallol by decomposing gallic acid.

Any ideas?

[Edited on 6-22-2012 by White Yeti]

bbartlog - 24-6-2012 at 13:11

Boiling with dilute HCl should do the trick. See e.g. http://www.springerlink.com/content/g25u410p05336281/ (I can only see the first page but it already includes a bit of the experimental).

S.C. Wack - 24-6-2012 at 16:24

http://www.sciencemadness.org/talk/viewthread.php?tid=4051

White Yeti - 24-6-2012 at 18:58

Good stuff bibliomaster. Between the time I posted this and now I tried the hydrolysis with sodium bisulphate and it seemed to work. Now I'm

confronted with the challenge of separating gallic acid from a whole host of organic chemicals, some soluble and others not.

garage chemist - 24-6-2012 at 20:00

I have a german procedure for gallic acid from tannin that uses alkaline hydrolysis.

Short summary in English:

25g tannin is dissolved in 25ml hot water and a solution of 15g NaOH in 25ml water is added, along with 0,5ml of saturated sodium bisulfite as a

simple oxygen scavenger.

The solution is stirred and held at 60-70°C for 3-4 hours, adding a few drops of bisulfite every hour.

After cooling, 35ml water is added and the crude gallic acid precipitated by acidification with conc. HCl.

After standing for one day it is filtered with suction and the brown-black solid recrystallized from four times its own weight of water to which 1ml

aqueous SO2 solution, 2ml 25% HCl and some powdered activated charcoal have been added.

The solution is filtered quickly through a folded paper filter while hot. Almost colorless gallic acid crystallizes from the filtrate upon cooling.

If necessary, recrystallize a second time.

Dry at low temperature, not in a desiccator.

Yield 17-20g crude product. Contamination with iron must be carefully avoided.

Despite the procedure not specifying it, I highly recommend working under argon atmosphere as long as your solution is alkaline. I have a procedure

for the methylation of gallic acid with DMS in aqueous NaOH and it states that the solution immediately turns pitch black due to aerial oxidation when

the gallic acid is dissolved in NaOH, and that entry of oxygen into the flask must be avoided by working in a closed system.

I strongly doubt that the addition of bisulfite is enough to stop the alkaline gallate from getting oxidised to black gunk.

In the other thread there were mentioned possible side reactions of gallic acid during acidic hydrolysis that involve loss of the phenolic OH groups.

Be sure to verify the identity and purity of your product if you do the acidic hydrolysis.

If acidic hydrolysis doesn't give a good product, try the alkaline method that I posted.

I look forward to your results. I also have some tannin standing around that I've bought long ago and never came around to hydrolyzing it.

[Edited on 25-6-2012 by garage chemist]

White Yeti - 25-6-2012 at 08:58

Thanks GC. I don't have the reagents required for that procedure, but I'll see if I can get hold of them soon. That looks like a very worthwhile

procedure. I was afraid that the products might be air sensitive. I observed a colour gradient the aqueous phase after the "hydrolysis", perhaps

indicating a reaction with air. The gradient went from a dark yellow to dark red, the precipitate was dark brown. Perhaps the acids were not combining

with air too readily because I was using a weak acid for the hydrolysis?

I tested the precipitate after I filtered and washed it with water; it's soluble in ammonia giving a brown solution. I don't know if this is of any

help at all.

I mixed the aqueous layer with egg whites and the proteins precipitated out, indicating that tannins were still present in the aqueous phase.

I'm beginning to consider the possibility that the precipitate may be composed of gallic acid, not flavonoids.

My alternate hypothesis is that by adding sodium bisulphate, I might have decreased the solubility of gallic acid without disturbing the structure of

the tannic acid at all; no hydrolysis ever took place. This would explain why the aqueous phase behaved like a solution of tannins rather than gallic

acid.

garage chemist - 25-6-2012 at 09:13

The reaction with air is problematic only when the solution is alkaline.

It's the same as with hydroquinone: the crystallized compound and its neutral or acidic solutions are relatively air stable, but add NaOH and it turns

black within a few minutes if oxygen is present. With alkaline pyrogallol the oxygen uptake is so fast that it can be used to analytically determine

the oxygen concentration in gas mixtures. Gallic acid also has the three neighboring phenolic OH groups and reacts similarly.

Which reagents are you missing for that synthesis? Argon?

Did you measure the melting point of your product from the acidic hydrolysis?

White Yeti - 25-6-2012 at 11:08

I'm missing argon, NaOH, NaHSO3 and HCl :( Unfortunately, experimentation is viewed as more of an alchemy than a hobby in my household, so my

collection of chemicals is rather limited.

I didn't measure the melting point yet, I'm waiting for it to dry first. It's taking a while because of the humidity.

Do you think ammonia is alkaline enough to induce the reaction between gallic acid and oxygen? If so, I saw no reaction when I mixed the precipitate

with ammonia earlier on. I left it on air and made no effort to exclude it.

On the other hand, I mixed ammonia with the upper aqueous layer (where the gallic acid should have been in the first place) and I saw a very slight

darkening of the solution upon addition.

If it's relevant at all, I added 3% hydrogen peroxide and ammonia together to the "aqueous products solution" and nothing happened.

I'll see if I can upload a picture of all the tests I have done so far.

Boffis - 27-7-2012 at 22:07

I have actually tried the alkaline hydroylsis of tannin. I used wine-makers tannin from a home brew shop. I didn't have the benefit of

Garage_chemist's German preperation but I came up with a very similar "receipe". Here is my method and results:

20g of wine-makers tannin powder was dispersed into 25ml of 40% (note 1) and 25ml of water in a 100ml beaker. 0.5g of sodium metabisulphite (note 2)

were added as an antioxidant and heated to 60-70 C on a water bath for about 1.5 hours. After cooling a little 14ml of 28% hydrochloric acid and a few

drops of isopropanol were added (the latter to reduce the foaming). The mixture was covered with a watch glass and left to cool overnight. The brown

mass was stirred to produce a thick slurry and filtered at the pump, washed with 2 x 15ml of ice cold water and dry dried over heating pipes (about 35

C) for 24 hours. The yield of crude brown crystalline gallic acid was 11.36g.

The crude product was recrystallised from 30ml of water, 2ml of 28% hydrochloric acid, a pinch (<0.1g) of ascorbic acid and 0.5g of decolourizing

carbon and boil for 5 minutes before being filtered hot through a preheated buchner funnel. The pale brown solution was allowed to crystallize in a

beaker for several hours until it had reached ambient temperature (about 8 C) and filtered at the pump. The filter cake was washed with 2 x 10ml of

iced water and dried in a warm place as before; the yield was 6.09g of creamy buff coloured needles.

The initial filtrate was eveporated down in a shallow basin on the water bath after the addition of a future 0.1g of ascorbic acid to about 12-15ml

and allowed the crystallized, filtered and dried. The second crop of darker brown crystals of less pure gallic acid was 2.57g. This will be

recrystallized with the next batch prepared.

Note 1, I use and store sodium hydroxide as a 40% solution because in our damp climate attempt to measure out small weights of sodium hydroxide prills

tend to results in rapid caking, its much easier to weight out 400g and make up 1 L of solution. A 40% solution is approximately 10 Molar and the

sodium carbonate produced by adsorption of atmospheric COText is almost insoluble in such concentrated sodium hydroxide and sinks to the

bottom of the polythene bottle.

Note 2, Since sodium metabisulphite reacts immediately with sodium hydroxide to form sodium sulphite, clearly the later compound may also be used. Its

just that sodium metabisulphite is also available from homebrew shops. During my small scale orientation experiments I tried ascorbic acid and this

also appears to work as an antioxidant but I wasn't sure it would survive the long in the sodium hydroxide digestion.

In one of the books related to dye chemistry in the SM library there is a detailed hydrolysis with ammonia to produce both gallic acid and gallamide

(3,4,5 trihydroxybenzamide). I haven't tried it but I will.

Boffis - 15-7-2016 at 13:08

I know this is a long dormant thread but I recently had reason to prepare a significant amount of gallic acid from tannins and tannic acid. I used up

all of my existing tannic acid and purchased some more from a home brewing shop but the new tannin failed to yield gallic acid so I decided to

investigate the available sources of tannic acid from different supplier to see if I could determine how to identify tannins that yield gallic acid.

The failed batch was from a 50g pot of "tannic acid" from a home brewing shop that I just happened to spot while driving through another town, the

name on the label was Bigjugs Brewing though this was not, as far as I can recall, the name of the shop. While this material is presumably functional

as a fining agent for home wine makers it does not seem to yield gallic acid.

As a result of the problems encountered with the new source of tannic acid I purchased tannic acid and related tannins from several internet suppliers

and subjected them to an investigation to determine which sources provided the best tannic acid for gallic acid production. The results were rather

complex but interesting never-the-less and demonstrated that the commercially available tannins can be divided into two basic groups.

The tannins used in this experiment were as follows:

Tannic acid; from an Ebay supplier “Mineral Water”

Tannic acid; from another Ebay supplier “Anglia Chemicals” though this is not the name used on Ebay

Cutch; from “P & M Woolcraft” and is sold as a natural dyes for wool

Tannic acid; from a homebrew supplier “Bigjugs Brewing”

I included the “Cutch” or as it is sometimes known, catechu, because I was working on this material as a possible source of 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic

acid and phloroglucinol and it falls into the broader group of “tannin like materials”.

I first of all examined the powders dry. The Mineral Water tannic acid was the palest and the Anglia Chemicals tannic acid the darkest, almost like

coco powder. All are practically oderless or have at most a slight musty smell.

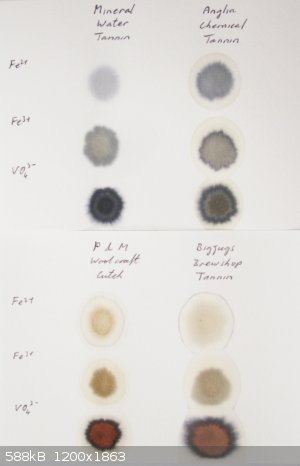

The tannin powders

Next a little of each (about the tip of a small spatula) was dissolved in deionised water and shaken until dissolved. The colours of the solutions

reflect the colour of the powders.

The tannin solutions

Various chemicals were tried on the aqueous solutions to try and find a characteristic reaction that might indicate the nature of substance and

therefore the likely yield of gallic acid. The most useful reactions were found to be iron salts (both ferric and ferrous), sodium vanadate and sodium

nitrite. The first three can be carried out as spot tests on filter paper while the nitrite test works best in a test tude with the addition of a

little mineral acid.

In spite of the apparent difference between the Mineral Water and Anglia Chemical tannic acids they gave remarkably similar results with the above

reagents. They gave blue spots with ferric and ferrous salts and a deep indigo blue spot with sodium vanadate. Interestingly the Anglia Chemicals

tannic acid gave a more intense colour with ferrous iron but a less intense colour with the vanadate solution.

The iron salt and sodium vanadate spot tests

By contrast the Bigjugs Brewing tannic acid gave almost no colour with ferrous iron, an olive green-grey colour with ferric iron and a brown colour

with sodium vanadate. It was pure chance that I decided to incorporate the P & M Woolcraft cutch for comparison but this proved very useful and

shows that the Bigjugs Brewing “tannic acid” is in reality a catechu type tannin and will not yield gallic acid on hydrolysis. It should yield

“protocatechuic acid” (3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid) and phloroglucinol but my experience is that it is more difficult to break down with hot alkali

solution. The spot test results are illustrated above.

The sodium nitrite test is carried out in a small test tude; a few drops of tannic acid solution are mixed with a drop of 5% sodium nitrite and then a

few drops of dilute mineral acid are added (2M HCl or HNO3 work admirably). The Mineral Water and Anglia Chemicals tannic acids effervesce copiously

and the solution turns a clear deep maroon red while the P & M cutch and the Bigjugs Brewing tannic acid give a medium brown precipitate.

Further preparations of gallic acid from both Mineral Water and Anglia Chemicals showed that both yield gallic acid on sodium hydroxide hydrolysis;

details will be posted, with photographs, in the Prepublication section shortly. Attempts to hydrolyse the catechu type tannins with sodium hydroxide

solution were unsuccessful but according to the literature (see Thorpe's Dictionary of Applied Chemistry) fusion with potassium hydroxide is generally

preferred for this process. I will attempt this and report back!

Conclusion

A simple spot test can be used to identify those tannins that will yield gallic acid on hydrolysis; either the ferrous sulphate test or the sodium

vanadate seem best suited to this purpose.

The paler Mineral Water tannic acid is the better form of tannic acid if required as a spot test reagent for vanadate ions. It also give a paler,

easier to purify gallic acid extract on hydrolysis and this results in a better yet due to less mechanical loss. On the down side though it is more

expensive than the Anglia Chemicals tannic acid.

Work continues to check and characterize the products of hydrolysis since some tannins contain more than one hydroxybenzoic acid.